Arguments and Information

5 Supporting Your Arguments with Quality Evidence

Learning Objectives

- Construct sound arguments

- Analyze arguments for their strengths and weaknesses

- Evaluate common types of evidence to assess their quality

- Explore effective language

Every day you make and encounter a variety of arguments. You might make an argument to your school’s student government to start an esports club. On a video chat with your parents, you might present an argument for why they should purchase you a car for school or send (more) spending money. Later that night, your friends might seek to convince you that LeBron James, rather than Michael Jordan, is the best basketball player of all time.

We also routinely encounter arguments about important civic matters. We might read a letter in the newspaper by a school board member arguing why a local property tax increase is necessary to improve area schools. On news programs and in public speeches, we daily hear politicians and political operatives advance arguments about the best way to run the country.

With so many different arguments competing for our adherence, how do we make decisions about personal matters, about what is best for our local community, and about what the nation should do on vital issues of the day?

This chapter enables you to think carefully about logos. Logos is the logical or reasoned basis of an appeal (i.e., argumentation), and it is part of the rhetorical canon of invention (explained in more depth in chapter 18). By learning more about argumentation, you will improve your ability to make sound decisions and critically analyze public options. You will also learn about speechmaking, since most speeches are based on a series of arguments. In this chapter, we examine two fundamental issues related to reasoning in public speaking: the structure of argument and the selection and evaluation of evidence.

Box 5.1 Ethos, Pathos, & Logos

Even though this chapter focuses on logos, all 3 rhetorical appeals are important for building strong, compelling arguments and crafting an effective speech.

Ethos, or establishing your credibility as a speaker, shows your audience that you are a trustworthy and reliable speaker. Using reliable and well-tested evidence is one way to establish ethos.

Pathos, or emotional appeals, allows you to embed evidence or explanations that pull on your audience’s heartstrings or other feelings and values.

Logos, using reason or logic, involves selecting logical evidence that is well-reasoned and free from fallacies (more in chapter 6).

The Structure of Argument

An argument is the advocacy of a belief, attitude, or course of action that is supported by evidence. An argument (or series of arguments) gives reasons why a listener should agree with the perspective being advocated. We begin by considering the development of what is known as the Toulmin model, and some limitations to the practice of good reasoning.

Box 5.2 Classical Reasoning

Aristotle advocated the syllogism as the proper form of argument. A syllogism is a three-step proposition that consists of two premises and a conclusion. If the premises are valid, then the conclusion must be true. This is also known as deductive reasoning, reasoning that moves from valid premises to a specific conclusion. The classic example of a syllogism is the following:

All men are mortal. (major premise)

Socrates is a man. (minor premise)

Therefore, Socrates is mortal. (conclusion)

If the two premises can be proven true, then it follows that the conclusion must also be true. This is also the process of formal logic, which relies on the certainty of the offered premises to reach what is considered an unquestioned, or true, conclusion (Toulmin, 1958, p. 122).

Syllogism is a valid argumentative form—as is deductive reasoning generally. However, in regular conversation, we rarely have premises and conclusions that are accepted as absolutely true. Just as often, some premises are omitted from an argument. Observing such tendencies, Aristotle coined the enthymeme as a rhetorical syllogism.

An enthymeme is an informal, incomplete syllogism in which a speaker relies on an audience to use its knowledge and experience to supply missing information that completes the argument. Take, for example, the underdeveloped argument, “Tax incentives for electric vehicles are justified because they will slow climate change.” Its central, unstated premises include “tax incentives influence consumer behavior” and “vehicle emissions contribute to climate change.” The enthymeme expects listeners to supply the missing reasoning that completes the argument.

However, these premises can also be debated or argued. Even if, as an audience member, we can supply a missing premise, we might still reject the argument. In this case, we might reject that “vehicle emissions contribute to climate change” or that the government should intervene in the free market. The contingent nature of premises in enthymemes allows for disagreement on public matters and policy decisions (Gage, 1996, pp. 223-25). Exceptions and counterarguments to premises and conclusions result in complex arguments that defy categorization in classical syllogistic form.

The Toulmin Model

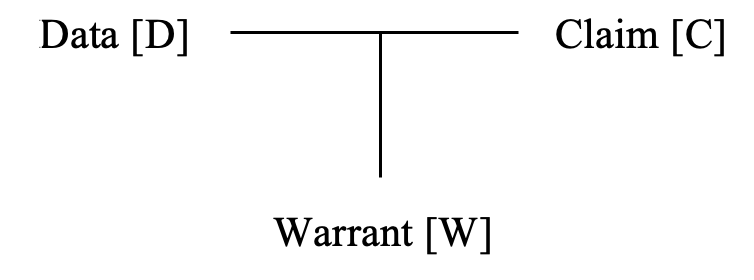

In the 1950s, Stephen Toulmin developed an approach to reasoning that is accepted by many as the standard in argument studies. This approach, popularly known as the Toulmin model, provides a way to understand and critique arguments. In its full form, the model consists of as many as seven parts (see box 5.3); however, we primarily focus on its three most central components: claim, data, and warrant.

Claim

The claim of an argument is what you are attempting to prove and want an audience to accept. Examples of claims include the following:

- “I should study chemistry this evening.”

- “My education will provide a good return on investment (ROI).”

- “My public speaking professor is the best.”

Your thesis statement is the most important claim in your speech. For instance, in a persuasive speech, you might offer the thesis “Greek organizations’ new member recruitment should be improved.” Each main point—each reason for changing Greek recruitment—is also a claim that supports your thesis. These are what we call subclaims because they are subordinate to the larger argument.

Box 5.3 The Toulmin Model

Born in London, Stephen Toulmin (1922–2009) studied mathematics and physics before turning to philosophy and a focus on ethics, logic, and reasoning after World War II. While Toulmin authored several books and taught at multiple US institutions, he is best known for the model of argument that came to be identified with his name.

In his 1958 book The Uses of Argument, Toulmin originally outlined an argument as consisting of six parts, but following the work of argumentation scholars Richard D. Rieke, Malcolm O. Sillars, and Tarla Rai Peterson (2009), we offer the full model as containing seven elements:

- Claim: The idea one is trying to prove and wants an audience to accept.

- Data: Material or evidence that supports the acceptance of the claim. It answers the question “Why?” or “What have you got to go on?”

- Warrant: A statement that justifies the connection between data and claim. The warrant is often implied and answers the question “How do you get there?”

- Backing: More specific evidence that reinforces data or the warrant. It explains the data or warrant as being “On account of.”

- Qualifier: A term that modifies the strength or certainty of the claim such as “might,” “usually,” or “always.”

- Reservation: A condition or exception when the claim would not be advocated. A reservation is noted by terms like “except” or “unless.”

- Rebuttal: A basis for challenging the validity of the claim.

Data

A claim alone is not an argument. A claim offered without reason, support, or data is merely an assertion. An assertion fails to qualify as an argument because no reason is given for why it should be accepted. This is why data, or material and reasons supporting the acceptance of the claim (also commonly called evidence), are essential in forming a valid argument. Note that “data” here refers to all types of evidence, not solely statistics and facts.

Data fill in the “why” or “because” for your claims. For your thesis that Greek organizations’ new member recruitment should be improved, data could consist of the following:

- statistics on recent challenges to new member recruitment

- testimony about unfair recruitment practices

- examples of problems with the recruitment system

Each piece of information allows you to better support the claim and more convincingly persuade an audience to accept your argument. Data are typically found throughout your speech.

Warrant

Finally, a valid argument rests upon an acceptable warrant. The warrant provides justification for using the data to support the claim. In essence the warrant is a bridge, often in the form of a value statement, that connects the data with the claim, reinforcing their relationship.

Warrants are typically implied rather than stated; however, at times it is important to state your warrant as well, particularly when an audience may not readily agree with the link between claim and data that you are otherwise asserting.

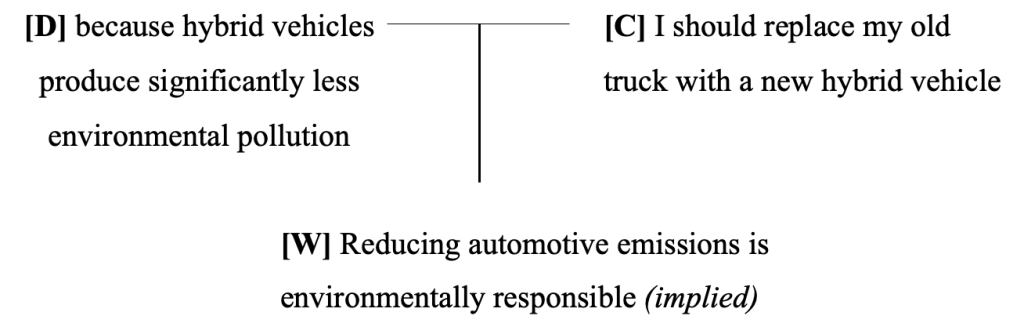

Consider the following example to understand how a warrant functions:

Claim: I should replace my old truck with a new hybrid vehicle

Data: because hybrid vehicles produce significantly less environmental pollution.

The warrant wants to answer how we get from the data to the claim or explain what makes this data a reason to accept the claim.

Warrant: Reducing automotive emissions is environmentally responsible.

It is likely that this warrant would be implied, relying on enthymematic reasons supplied by an audience. Presumably, the positive contribution to the environment is a strong enough incentive to cause the person making this argument to take action. However, there could be counterarguments or rebuttals that might cause this person to reject the claim (the cost of a new vehicle, for example). A more developed argument would consider these possibilities by providing backing for the warrant and/or data in quantifying the environmental benefits.

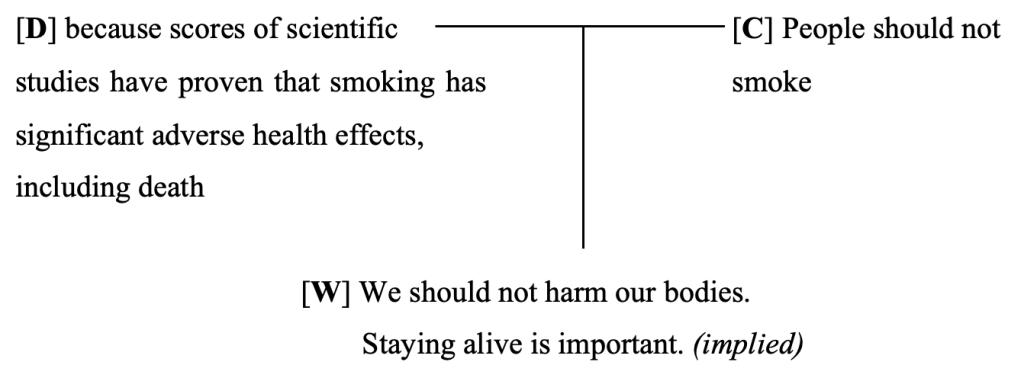

Box 5.4 Visualizing the Toulmin Model

The Toulmin model provides a layout to visualize or diagram arguments.

Example argument: I should replace my old truck with a new hybrid vehicle because hybrid vehicles produce significantly less environmental pollution.

The Toulmin model is more than a way of diagramming arguments—it is a way of improving how you think about arguments. It allows you to conceptualize and diagnose your own arguments and those produced by others. Putting an argument into the Toulmin form can allow you to

- see what the claim is and if it is reasonable;

- consider what the data are, if there is enough, and the data’s quality; and

- evaluate if there is a reasonable warrant, or one can be inferred, that connects the data and the claim.

Because the model promotes clearer thinking about how we reason together, it is a way of enriching our civic engagement and the messages we send and receive about democratic participation.

Arguments and Their Limits

Rhetorical arguments are powerful but inexact. Audiences can weigh arguments on public issues and come to significantly different conclusions about their merit. Such is the case in the difficult issue of abortion access as different people hold different views on the issue, and different states have vastly different laws.

Some audiences may also refuse to reason. As the example in box 5.5 illustrates, some appeals, urges, and habits overcome reason, and not all decision-makers weigh competing arguments the same way.

Box 5.5 Limitations on Arguments Against Smoking

Think about this abbreviated (and asserted) causal argument: “People should not smoke because scores of scientific studies have proven that smoking has significant adverse health effects, including death.” In a Toulmin form, the argument would appear as follows:

A wealth of valid backing for this argument is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other sources. Yet many people who hear the strong evidence against it still smoke. The American Cancer Society reports that as of 2019, approximately thirty-four million people in the United States (14% of the population) smoke. The reasons are no doubt varied, including value hierarchies that justify the decision to smoke, challenges to the evidence concerning the impacts of smoking, and the difficulty of kicking the habit.

A wealth of valid backing for this argument is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other sources. Yet many people who hear the strong evidence against it still smoke. The American Cancer Society reports that as of 2019, approximately thirty-four million people in the United States (14% of the population) smoke. The reasons are no doubt varied, including value hierarchies that justify the decision to smoke, challenges to the evidence concerning the impacts of smoking, and the difficulty of kicking the habit.

Evidence and Its Evaluation

Evidence is data and backing in the form of examples, statistics, and testimony that are used to support a claim. The key is finding not just any evidence but the best evidence to support your argument. When you use weak evidence, your data will generally be insufficient to convince an audience of your argument’s validity.

To discover strong evidence, begin by selecting credible sources using the guidance in chapter 4. Then draw from your sources to find and evaluate evidence. Use the instructions provided next for choosing examples, scrutinizing statistics, and selecting testimony.

Choosing Examples

An example provides a concrete instance in the form of a fact or occurrence. An example seeks to make a claim tangible to an audience. Examples generally take one of three forms: specific, hypothetical, and anecdotes.

Specific Examples

The most valuable type of example is a specific example. A specific example is factual, one that has actually happened or is being experienced. A specific example prompts an audience to recognize that the claim (or a similar claim) has been demonstrated or proven true on a prior occasion.

Box 5.6 Specific Examples in Practice

In a 2023 commencement address at the University of Chicago, Brett Stephens, a New York Times columnist and Chicago graduate, gave a speech that argued for the value of “speaking your mind when other people don’t want you to.” One way he supported his thesis was through the use of a series of specific examples in which conventional wisdom proved incorrect and it would have been beneficial to interrogate the ideas of allies or superiors, including the following:

Why were the economists and governors at the Federal Reserve so confident that interest rates could remain rock bottom for years without running a serious risk of inflation?…Why were so few people on Wall Street betting against the housing market in 2007? Why were so many officials and highly qualified analysts so adamant that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction?…and why did so many major polling firms fail to predict Donald Trump’s victory in 2016?

The effectiveness of Stephens’s examples was in their succinct expression of a series of specific instances where most experts were ultimately proven incorrect and more dissenting voices would have been valuable.

Hypothetical Examples

A less powerful but still useful type of example is a hypothetical example. A hypothetical example is based on a plausible event or occurrence but does not represent a specific, actual instance. This sort of example allows an audience to visualize the claim, but it lacks the concrete data of a specific example.

Box 5.7 Hypothetical Examples in Practice

In 2023 when former South Carolina governor and US ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley announced her intention to run for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination, she spoke of her desire to create a country where “anyone can do anything and achieve their own American dream.” To illustrate her claim, Haley pointed to a plausible range of American experiences, without naming any one individual in particular as possessing the experiences:

The college student who’s paying too much and getting too little from her education. The young adult in his first real job wondering how he’ll ever afford a mortgage or start a family. The single mom working two jobs and three times harder than anyone else.…I’m fighting for all of us because all of us have to be in this together.

Haley used hypothetical examples that allowed her audience to visualize themselves within the America she was seeking to lead.

Anecdotes

Finally, anecdotes, which we defined in chapter 2 as stories or extended examples in narrative form, are more elaborate examples that include additional detail. Often presented in the form of personal narratives, these examples seek a deeper connection with the audience. While powerful, these take time for a speaker to develop and present.

Box 5.8 Anecdotes in Practice

An effective illustration or personal narrative is again found in Nikki Haley’s presidential campaign announcement. Three times in that speech Haley returned to her status as “the proud daughter of Indian immigrants” to illustrate the relevance of her personal experience in leading “a new generation” of Americans “into the future.” The extended example peaked near her conclusion where she underscored her experiences a final time. Speaking about the “country’s renewal,” she shared,

I’m more confident than ever that we can make this vision real in our time because that’s what I’ve seen my entire life. As a brown girl growing up in a black and white world, I saw the promise of America unfold before me. As the proud wife of a combat veteran, I saw our people’s deep love of freedom and our determination to defend it. As governor I saw our state move beyond hate and violence and lift up everyone in peace.…The time has come to renew that spirit and rally our people. Our moment is now.…Let’s save our country…and move forward together.

Here Haley offers an illustration of her life experiences that is richer than any specific accomplishment she has had as a politician and provides insight into her life.

Not all examples are equal, and thus you must carefully evaluate their selection. A poor example fails to justify your claim and risks damaging your credibility and persuasiveness.

Here are a few considerations (also found in box 5.16) that you should make when selecting and evaluating examples:

- Is the example representative, or typical, of the broader situation or experience?

- Are a sufficient number of examples used to prove the claim?

- Have negative examples (counterexamples) been addressed?

- Is the example compelling in its detail, clarity, and vividness?

Consider these questions when evaluating the strength of an example, though an example may not meet all of these standards and still be satisfactory.

Box 5.9 Examples as Evidence

An example provides a concrete instance in the form of a fact or occurrence. It seeks to make a claim tangible to an audience. Examples generally take one of three forms.

- Specific example: A specific example is factual, an example that has actually happened or is being experienced.

- Hypothetical example: A hypothetical example is based on a plausible event or occurrence but does not represent a specific, actual instance.

- Anecdote: Anecdotes, extended examples, or illustrations are more elaborate examples that contain additional detail.

Scrutinizing Statistics

Statistics, a second common form of evidence, represent information in numeric form according to size, quantity, or frequency. In public speaking, statistics are most commonly used to demonstrate public opinion, capture common experiences and behaviors, and efficiently express the distribution and allocation of resources.

Speakers love statistics—and with a little searching, it seems we can find a statistic for just about anything, from the number of pieces of mail processed and delivered every day by the US Postal Service (318 million) to the percentage of people who believe in extraterrestrials (about 65% of adults in the United States).

Because statistics have an air of tangibility, appear to be exact, and seem authoritative, we too often accept them as true. In reality, statistics should be carefully scrutinized. As American author and satirist Mark Twain is purported to have once said, “There are lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Nonetheless, statistics are a useful basis of proof in many speeches.

Box 5.10 Statistics in Practice

In his April 3, 2024, remarks at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome H. Powell relied on statistics in advancing his case that the nation’s economic outlook was continuing to improve after a period of stubbornly high inflation. Powell supported his contention by pointing to improvements in inflationary trends and continued job growth.

- Specifically, Powell noted that inflation had slowed from an annual rate of 5.2% in the prior year to only 2.5% in the twelve-month period leading to February 2024.

- Moreover, three million new jobs had been created in 2023 as inflation declined, and an average of 265,000 new jobs were added in the previous three months.

- Due to such changes, the Federal Open Market Committee predicted continual, if “sometimes bumpy,” progress toward the Fed’s goal of 2% annual inflation.

These statistics, which reflect the use of raw numbers, trends, and averages, were some of the primary data offered by Powell as he addressed the overall health of the US economy

Four of the most common forms of statistics called upon by public speakers are averages, raw numbers, trends, and polls.

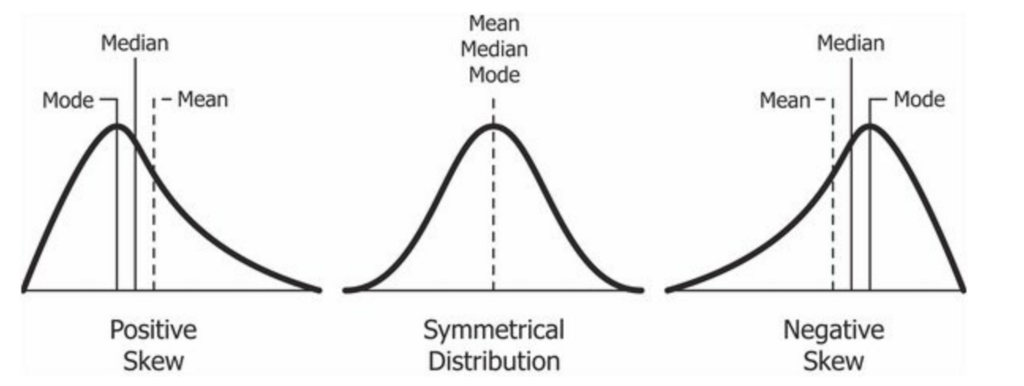

Average

An average is a common and seemingly benign statistic that is frequently used by speakers. In principle it represents what is typical—what is average—and in box 5.10, we see Federal Reserve Board Chair Powell making use of the average number of new jobs being added to the economy on a monthly basis—265,000. However, an average may be more complicated than it initially appears because there are at least three methods for determining an average—through mean, median, or mode.

The most common method for representing an average is the mean. A mean is derived by summing all the data and dividing the total by the number of data points. The median, in contrast, is the data point that appears in the exact middle of a sample, and the mode is the result number that appears most frequently.

Box 5.11 Limitations of Using the Mean to Find an Average

Suppose you were leading a discussion about the low working wages available for college students seeking summer employment. A statistic you might find valuable is the amount earned by the average student worker in your class during the previous summer (this would be a small sample but a relevant one to your audience).

If you had access to all the financial data, you could determine the mean income by adding together the total dollars earned by your classmates and then dividing it by the number of student workers. If twenty-five students had combined wages of $150,000, the mean student income was $6,000. Seems clear enough, right? However, what if you found that this included $50,000 earned by a single student in an astoundingly successful entrepreneurial venture? How does this change the average, and what does it do to the value, meaning, and accuracy of this statistic for your speech?

Raw Number

A second common statistic is a raw number. In the student wages example in box 5.11, the raw number was $150,000 (the total wages earned). In box 5.10, Jerome Powell made use of a raw number as well—three million jobs added in the previous year. We use raw numbers when we want to draw on the power of the magnitude of a number. An average may make a number seem small or insignificant, but by giving the entire scope of the data through a raw number, an audience may gain a better grasp of the situation.

However, the opposite may also be true: A raw number can make a problem look much worse than it actually is because it combines all the data into a single representation. Box 5.12 provides an example.

Box 5.12 Limitations of Using Only Raw Numbers

If you were to learn that the Biden administration proposed a $34 billion increase (a raw number) to the United States’ 2025 defense budget, you might be concerned about the seemingly large budget increase. However, if you also were provided with a trend statistic clarifying this represented a budget increase of only about 4.1%—and that after accounting for inflation over the prior two years the spending power of the defense budget experienced a 3% decline—you might perceive the raw number differently

Trend Statistic

When a speaker wants to demonstrate a change that has occurred over a period of time, the statistic that is most often used is called a trend. A trend statistic emphasizes change in a clear and meaningful way by providing two points of comparison. As the Powell example in box 5.10 demonstrates, trend statistics are important to economists. Trend statistics for inflation, gross domestic product, unemployment, and interest rates can provide a more focused and efficient evaluation of the immediate economic climate.

Polling Data

Finally, perhaps the most popular type of statistic is polling data. A valid, scientific poll measures the opinions or beliefs of a large group of people by collecting data from a representative random sample that is similar in its demographics to the rest of the population and then generalizes the results.

Polling data is collected on a variety of topics, ranging from whom one intends to vote for in a presidential election to what is the best movie ever made. One of the oldest and most recognized polling researchers is Gallup, a global analytics firm that has measured public opinion for nearly a century. Gallup regularly tracks opinions on various topics, such as consumer confidence, presidential approval, and the future of Medicare and Social Security. While polling data must be carefully analyzed, it is valuable in giving your audience an indication of what a larger public thinks. That is, while the majority may not always be right, their opinion can be influential.

However, not all polls are equally valid, and in selecting polling data, there are several items you should consider:

- In particular, you should verify that the poll is based on a representative random sample. This can be determined by examining how the poll was conducted—who was polled, how they were polled, how many people were polled, when they were polled—and what the margin of error is. The margin of error is the uncertainty or potential variation in a polling result. It reflects the sampling error or margin in which there is less confidence about the accuracy of the survey result.

- Also, be careful how you use nonscientific internet polling that asks website visitors their opinion on an issue. Such polls have a selection bias in terms of who chooses to take the poll. For example, The Athletic’s daily sports newsletter, “The Pulse,” periodically gives sports fans the opportunity to express their opinion on various sports-related issues and events. Such polls are interesting to sports fans and do show something of popular opinion, but be mindful that the results are not statistically valid.

Box 5.13 The American Freshman

The Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP) Freshman Survey, administered by the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA, is taken by tens of thousands of first-time full-time college students each fall. In 2019, 126,642 new students from 178 four-year schools participated in the survey. Ninety-five thousand of those students from 148 institutions were included in the normative data that was reported. Among the results are the following:

- Getting a better job was identified as a “very important” reason to attend college by 83.5% of respondents.

- Making more money was named as a “very important” reason to attend college by 73.2% of respondents.

- A personal goal of being well-off financially was indicated by 84.3% of respondents.

- A significant portion of respondents, specifically 43.6%, perceived themselves as “middle-of-the-road” politically.

|

Issue |

2019 Respondents Indicating Agree Strongly or Agree Somewhat |

2015 Respondents Indicating Agree Strongly or Agree Somewhat |

2012 Respondents Indicating Agree Strongly or Agree Somewhat |

|

Abortion should be legal. |

73.1% |

63.6% |

61.1% |

|

Students from disadvantaged social backgrounds should be given preferential treatment in college admissions. |

X |

52.3% |

41.9% |

|

Racial discrimination is no longer a major problem in America. |

X |

18.6% |

23% |

|

Same-sex couples should have the right to legal marital status. |

X |

81.1% |

75% |

|

Colleges have the right to ban extreme speakers from campus. |

51% |

43.2% |

X |

- What other information would you want to know about the data before deciding whether to use it?

- How useful might this information be to a speaker planning a presentation on a related topic?

- How might the information be misused or overgeneralized?

- What information do these results leave out?

In sum, it is crucial that you carefully scrutinize statistics. You should closely consider how a statistic was derived so you have a good grasp of its validity. It is ethically suspect to simply report a number without some understanding of how it was derived. Similarly, as a listener, be skeptical of statistics presented without enough information or context to evaluate their credibility. A statistical conclusion is only as good as the method used to arrive at it. For that reason, here are a few questions (also in box 5.16) you should ask when selecting and evaluating statistics:

- If the number is an average, is it the mean, the median, or the mode? Is it representative of the data, or is it skewed by an extreme data point?

- What was the sample size: the number of people used to determine the average or polled?

- If using polling data, what is the margin of error or reliability? Polls that have a margin of error greater than a few percentage points are suspect, particularly if the margin of error is greater than the difference between the polling result options.

- What do you know about the sample? Was it randomly selected? Are there factors about the sample population (age, gender, geography, etc.) that make the data suspect?

- When was the data collected? Public opinion, averages, and raw numbers can change with time.

Box 5.14 Statistics as Evidence

A statistic represents information in numeric form according to size, quantity, or frequency. A statistic has an aura of certainty and exactness while being able to efficiently express public opinion, capture common experiences, or show the scope of an issue. Statistics may be expressed in several forms.

- Raw number: A single number or figure that captures the breadth of an occurrence.

- Trend statistic: A trend statistic represents meaning over a specific period of time.

- Polling data: Polling data seeks to represent the opinions or beliefs of a large group of people by collecting data from a representative random sample.

- Average: An average seeks to numerically represent what is a typical or common experience. An average may be derived in three different ways.

- The mean is calculated by adding together all the data and dividing the sum by the total number of data points. Within the mean might be outliers—experiences that are either much larger or much smaller than what is typical.

- The median seeks to compensate for outliers by representing the data point that is in the exact middle of the sample; it is the middle result from among all of the data points.

- The mode is the data point that appears most frequently in the sample.

Selecting Testimony

Testimony is a third common form of evidence that serves as data and backing for arguments. Testimony is facts or opinions drawn from the words, experiences, and expertise of another individual. Testimony is used to supplement our own opinions and experiences.

Testimony should come from authoritative sources on an issue. In chapter 4, we recognized three types of source authorities. Subject authorities are sources with trained expertise on the topic. Societal authority emphasizes a source’s power to control outcomes based on their position within a society or organization. Authority can also be accrued through special experiences.

Suppose you are giving a speech on US immigration from Venezuela. You may have sensible ideas, but your audience is unlikely to accept your opinions alone. Instead, you should build your credibility by supplying well-informed testimony as data for your claims. Perhaps you could draw on testimony from the following:

- subject authorities such as Dr. Christopher Salas-Wright, whose research focuses on Latin American migrants

- societal authorities such as the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit organization

- authorities from special circumstances like a Venezuelan who immigrated to the United States

Testimony from such figures about the wisdom of your proposal would significantly aid the power of your argument.

Effective testimony provides explanation and analysis. Make clear how and why the source is authoritative on the issue. Then offer a sufficient amount of testimony to make the evidence compelling. For example, saying that an economic analyst declared “The current economic recovery will not continue” does not say much. The testimony fails to provide an explanation or analysis for why this perspective is justified.

Box 5.15 Testimony in Practice

In a 2011 speech on voter registration and rights, then–Attorney General Eric Holder used testimony to support his contention that voting rights are important and in need of attention.

Near the start of his address, Holder quoted former President Lyndon B. Johnson as saying, “The right to vote is the basic right, without which all others are meaningless.” Holder drew from Johnson’s authority as the president who in 1965 signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

In turn, to establish that there was a threat to this essential right, Holder drew from US Congressman John Lewis, a civil rights leader from the 1960s with firsthand knowledge and experience of the struggles over voter registration and voting rights. Holder quoted Lewis to supply testimony that voting rights are “under attack…[by] a deliberate and systematic attempt to prevent millions of elderly voters, young voters, students, [and] minority and low-income voters from exercising their constitutional right to engage in the democratic pro[cess].”

In this way Attorney General Holder, himself a credible source based on his title and position, enhanced his argument through the use of testimony.

As with the other forms of evidence, there are some considerations to make (also in box 5.16) when selecting and evaluating testimony:

- Is the source a qualified authority due to their subject expertise, societal position, or special circumstances? The testimony will strengthen your speech only if the source can truly add insight based on their status as a qualified authority on the topic being addressed.

- Does the source have firsthand knowledge of the issue? Ideally, the testimony is based on experience rather than opinion, and the source has had close dealings with the issues you are addressing.

- Does the source have excessive personal interest in the issue? A conflict of interest might overly bias the source’s testimony.

- What assumptions are made in the testimony? Consider what the source assumed when they made the comments and consider whether those assumptions are consistent with your own assumptions and argument.

Examples, statistics, and testimony are necessary components of valid arguments as they provide the substance used to demonstrate claims. Effective speakers use all three types of evidence in their presentations. Box 5.16 summarizes useful guidelines for selecting and evaluating examples, statistics, and testimony as you build and listen to speeches and arguments.

Box 5.16 Guidelines for Selecting and Evaluating Evidence

|

Universal Criteria |

Using Examples |

Using Statistics |

Using Testimony |

|

|

|

|

Using Language Effectively

Examples, statistics, and testimony make for solid evidence when building valid arguments. However, a speech is much more than just plopping in these forms of evidence (how boring, huh?).

When we craft arguments, it’s tempting to view our audience as logic-seekers who rely solely on rationality, but that’s not true. Instead, Walter Fisher (1984) argues that humans are storytellers, and we make sense of the world through good stories. A good speech integrates argumentative components while telling a compelling story about your argument to the audience. A key piece of that story is how you craft the language—language aids in telling an effective story.

We’ll talk more about language in Chapter 9, but there are a few key categories to keep in mind as you construct your argument and story.

Language: What Do We Mean?

Language is any formal system of gestures, signs, sounds, and symbols used or conceived as a means of communicating thought, either through written, enacted, or spoken means. Linguists believe there are far more than 6,900 languages and distinct dialects spoken in the world today (Anderson, 2012). Despite being a formal system, language results in different interpretations and meanings for different audiences.

It is helpful for public speakers to keep this mind, especially regarding denotative and connotative meaning. Wrench, Goding, Johnson, and Attias (2011) use this example to explain the difference:

When we hear or use the word “blue,” we may be referring to a portion of the visual spectrum dominated by energy with a wave-length of roughly 440–490 nanometers. You could also say that the color in question is an equal mixture of both red and green light. While both of these are technically correct ways to interpret the word “blue,” we’re pretty sure that neither of these definitions is how you thought about the word. When hearing the word “blue,” you may have thought of your favorite color, the color of the sky on a spring day, or the color of a really ugly car you saw in the parking lot. When people think about language, there are two different types of meanings that people must be aware of: denotative and connotative. (p. 407)

Denotative meaning is the specific meaning associated with a word. We sometimes refer to denotative meanings as dictionary definitions. The scientific definitions provided above for the word “blue” are examples of definitions that might be found in a dictionary. Connotative meaning is the idea suggested by or associated with a word at a cultural or personal level. In addition to the examples above, the word “blue” can evoke many other ideas:

- State of depression (feeling blue)

- Indication of winning (a blue ribbon)

- Side during the Civil War (blues vs. grays)

- Sudden event (out of the blue)

- States that lean toward the Democratic Party in their voting

- A slang expression for obscenity (blue comedy)

Given these differences, the language you select may have different interpretations and lead to different perspectives. As a speechwriter (and communicator), being aware of different interpretations can allow you select language that is the most effective for your speaking context and audience.

Using Language to Craft Your Argument

Have you ever called someone a “wordsmith?” If so, you’re likely complimenting their masterful application of language. Language is not just something we use; it is part of who we are and how we think. As such, language can assist in clarifying your content and creating an effective message.

Achieve Clarity

Clear language is powerful language. If you are not clear, specific, precise, detailed, and sensory with your language, you won’t have to worry about being emotional or persuasive, because you won’t be understood. The goal of clarity is to reduce abstraction; clarity will allow your audience to more effectively track your argument and insight, especially because they only have one chance to listen.

Concreteness aids clarity. We usually think of concreteness as the opposite of abstraction. Language that evokes many different visual images in the minds of your audience is abstract language. Unfortunately, when abstract language is used, the images evoked might not be the ones you really want to evoke. Instead, work to be concrete, detailed, and specific. “Pity,” for example, is a bit abstract. How might you describe pity by using more concrete words?

Clear descriptions or definitions can aid in concreteness and clarity.

To define means to set limits on something; defining a word is setting limits on what it means, how the audience should think about the word, and/or how you will use it. We know there are denotative and connotative definitions or meanings for words, which we usually think of as objective and subjective responses to words. You only need to define words that would be unfamiliar to the audience or words that you want to use in a specialized way.

Describing is also helpful in clarifying abstraction. The key to description is to think in terms of the five senses: sight (visual: how does the thing look in terms of color, size, shape); hearing (auditory: volume, musical qualities); taste (gustatory: sweet, bitter, salty, sour, gritty, smooth, chewy); smell (olfactory: sweet, rancid, fragrant, aromatic, musky); and feel (tactile: rough, silky, nubby, scratchy).

If you were, for example, talking about your dog, concrete and detailed language could assist in “bringing your dog to life,” so to speak, in the moment.

- Boring and abstract: My dog is pretty great. He is cute, friendly, and a little loud. I get a lot of compliments about him and he loves dog chews.

- Concrete and descriptive: Gordo, my grey and white Miniature Schnauzer, is a unique, ornery, and loving pup. He likes to lay on top of people as if he is giving them a full body hug and he wiggles his little tail nub when he’s happy. He protects the house by barking at anything that moves, yet he cowers in the corner when he hears loud noises. Gordo is the perfect mix of loyal and goofy, and he emits pure joy when he is chewing on a bully stick.

Doesn’t the second description do Gordo more justice? Being concrete and descriptive paints a picture for the audience and can increase your warrant’s efficacy. Being descriptive, however, doesn’t mean adding more words. In fact, you should aim to “reduce language clutter.” Your descriptions should still be purposeful and important.

Be Effective

Language achieves effectiveness by communicating the right message to the audience. Clarity contributes to effectiveness, but effectiveness also includes using familiar and interesting language.

Familiar language is language that your audience is accustomed to hearing and experiencing. Different communities and audience use language differently. If you are part of an organization, team, or volunteer group, there may be language that is specific and commonly used in those circles. We call that language jargon, or specific, technical language that is used in a given community. If you were speaking to that community, drawing on those references would be appropriate because they would be familiar to that audience. For other audiences, drawing on jargon would be ineffective and either fail to communicate an idea to the audience or implicitly community that you haven’t translated your message well (reducing your ethos).

In addition to using familiar language, draw on language that’s accurate and interesting. This is difficult, we’ll admit it! But in a speech, your words are a key component of keeping the audience motivated to listen, so interesting language can peak and maintain audience interest.

Active language is interesting language. Active voice, when the subject in a sentence performs the action, can assist in having active and engaging word choices. An active sentence would read, “humans caused climate change” as opposed to a passive approach of, “climate change was caused by humans.” Place subjects at the forefront.

You must, however, be reflexive in the language process.

Practicing Reflexivity

Language reflects our beliefs, attitudes, and values – words are the mechanism we use to communicate our ideas or insights. As we learned in Chapter 1, communication both creates and is created by culture. When we select language, we are also representing and creating ideas and cultures – language has a lot of power.

To that end, language should be a means of inclusion and identification, rather than exclusion.

You might be thinking, “Well I am always inclusive in my language,” or “I’d never intentionally use language that’s not inclusive.” We understand, but intention is less important than effect.

Consider the term “Gen Z”— a categorization that refers to a particular age group. It can be useful to categorize different generations, particularly from a historical and contemporary perspective. However, people often argue that “Gen Z is the laziest generation” or “Gen Zs have no work ethic!” In these examples, the intention may be descriptive, but they are selecting language that perpetuates unfair and biased assumptions about millions of people. The language is disempowering (and the evidence, when present, is weak).

Language assists us in categorizing or understanding different cultures, ideas, or people; we rely on language to sort information and differentiate ourselves. In turn, language influences our perceptions, even in unconscious and biased ways.

The key is to practice reflexivity about language choices. Language isn’t perfect, so thinking reflexively about language will take time and practice.

For example, if you were crafting a hypothetical example about an experience in health care, you might open with a hypothetical example: “Imagine sitting for hours in the waiting room with no relief. Fidgeting and in pain, you feel hopeless and forgotten within the system. Finally, you’re greeted by the doctor and he escorts you to a procedure room.” It’s a great story and there is vivid and clear language. But are there any changes that you’d make to the language used?

Remember that this is a hypothetical example. Using reflexive thinking, we might question the use of “he” to describe the doctor. Are there doctors that are a “he”? Certainly. Are all doctors a “he”? Certainly not. It’s important to question how “he” gets generalized to stand-in for doctors or how we may assume that all credible doctors are men.

Practicing reflexivity means questioning the assumptions present in our language choices (like policemen rather than police officers). Continue to be conscious of what language you draw on to describe certain people, places, or ideas. If you aren’t sure what language choices are best to describe a group, ask; listen; and don’t assume.

Conclusion

Arguments form the basis of decisions we make daily; thus, the ability to produce high-quality arguments is of vital concern to public speaking and civic participation. In this chapter you have learned the fundamental elements of argument and how to support them. Remember, too, that language plays a central role in telling a compelling story. Up next: organizing and then outlining your speech.