Approaches

16 Deliberative Discussions

Learning Objectives

- Accurately describe the goals of a deliberative discussion

- Identify historical uses of deliberative discussion

- Demonstrate five intellectual virtues as participants in a deliberative discussion

- Avoid using calls for civil conversations to quell disagreement and maintain the status quo

You have likely witnessed or participated in a debate. Perhaps you watched US presidential candidates like Kamala Harris and Donald Trump debate over foreign policy, or maybe you watched Stephen A. Smith and Chris Russo debate the merits of the Dallas Cowboys front office on First Take. If so, you know that debates typically feature clashing arguments for and against a topic. They tend to emphasize disagreements between two sides and imply that one position is a winner and the other is a loser.

You probably have not watched or participated in a deliberative discussion. In contrast to debate, a deliberative discussion encourages thoughtful investigation of multiple approaches to improving a public issue. As we will explain, it takes dedicated work and planning to organize a deliberative discussion, and it typically requires guidance from facilitators.

We will begin this chapter by identifying the major goals of a deliberative discussion. We will then introduce you briefly to the history of deliberative discussions in the United States. Next, the chapter will identify five intellectual virtues that participants in deliberative discussions should adopt to help ensure productive conversations. The chapter will end by considering the general benefits and limitations of deliberative discussions.

Goals of Deliberative Discussions

In chapter 15, we defined a deliberative discussion as a group conversation through which a community, guided by one or more moderators, examines a complex public problem and a range of available solutions to ultimately arrive at a choice or conclusion. We explained that the deliberative discussion nearly always follows some type of deliberative presentation (though both may vary in format and timing). Together, the deliberative presentation and subsequent discussion form the deliberative process, or what some people refer to simply as deliberation.

A deliberative discussion strives to produce both public knowledge and public judgment. Let’s talk briefly about each goal.

Public Knowledge

Public knowledge refers to participants’ shared and improved understanding of the wicked problem and possible solutions as they offer and hear multiple points of view. Recall standpoint theory from the previous chapter, which posits that our embodied identities and experiences influence our knowledge of the world and our perceptions of what is “true” or “normal.”

By hearing and genuinely considering viewpoints, experiences, and values from participants with differing standpoints, deliberative discussion shifts us from our individual, partial knowledge to a shared, public knowledge that is more robust. Public knowledge develops as we, together, better recognize the complexity of problems, the merits of alternative views, and the demerits of our originally preferred solution.

Box 16.1 Goals of Deliberative Discussions

- produce public knowledge: participants’ shared and improved understanding of the wicked problem and possible solutions as they offer and hear multiple points of view

- produce public judgment: the community’s thoughtful choice about its desired approach or next steps to address the problem based on the public knowledge developed during the discussion

Public Judgment

A deliberative discussion’s ultimate goal is to produce public judgment. Public judgment is the community’s thoughtful choice about its desired approach or next steps to address the problem. Public judgment is based on the public knowledge developed during the discussion.

A deliberative discussion’s ultimate goal is to produce public judgment. Public judgment is the community’s thoughtful choice about its desired approach or next steps to address the problem. Public judgment is based on the public knowledge developed during the discussion.

Two elements are worth noting here: First is that the group’s choice comes after they have produced public knowledge. That timing helps prevent what modern psychology scholars call groupthink, which is a phenomenon that occurs when members’ desire for harmony outweighs their willingness to critically examine alternative perspectives. Such critical examination (including scrutiny and disagreement) is required in a deliberative discussion.

The second aspect worth noting is that a deliberative discussion seeks to move participants to choice making. The ultimate goal of a deliberative discussion is for participants to choose the next best step(s) to solve the problem and ease the controversy, having considered the trade-offs of at least three broad approaches.

The next steps chosen can vary widely, such as adopting a particular approach, exploring new options, or finding answers to questions raised during the discussion. Naturally, participants in a deliberative discussion will not always come to an agreement about the next step(s) to take. But because they have thoughtfully considered the options and competing interests together, each will be prepared to advance a thoughtful proposal.

The “Public” in Public Knowledge and Public Judgment

Box 16.2 What is a “Public”?

A public refers to a collection of people who are joined together in a cause of common concern. Often a public works together to address an issue or question that affects their community. As a college student, you may consider the many publics of which you are likely a member: your residence hall or fraternity; your clubs, athletic teams, or student governance organizations; and even your major. Student athletes at your university, for example, may function as a public when they discuss, together, how they can travel to away games without missing too many classes.

In our definition, a public is distinctly different from a group of individuals. We might conceive of their differences in the following ways:

|

Individuals in a Group |

Members of a Public |

|

View themselves as separate entities or opposed sides |

Recognize their interdependency and common group identity |

|

Are driven by their own interests or needs |

Consider their own needs as well as those of fellow members, especially when needs conflict |

|

Usually believe their needs or concerns are in competition with other people’s needs and concerns |

Acknowledge the impacts of problems and attempted solutions beyond their own personal experiences and interests |

|

Think in terms of “me” versus “them” |

Think in terms of “us” |

|

Analogy: Competitors on a reality television show |

Analogy: Members of a sports team |

Keep in mind that the “public” in public knowledge and public judgment signals that a public is required to produce each together as a group. A public refers to a collection of people who are joined together in a cause of common concern. Thus, public knowledge and public judgment can only be achieved by such a collection of people. These goals cannot be attained by individuals working alone. Box 16.3 offers an example of a public that engaged in deliberative discussion. In the next section, we look back historically to recognize the long legacy of deliberative discussions to aid public decision-making.

Box 16.3 Public Knowledge and Public Judgment in a Deliberative Discussion

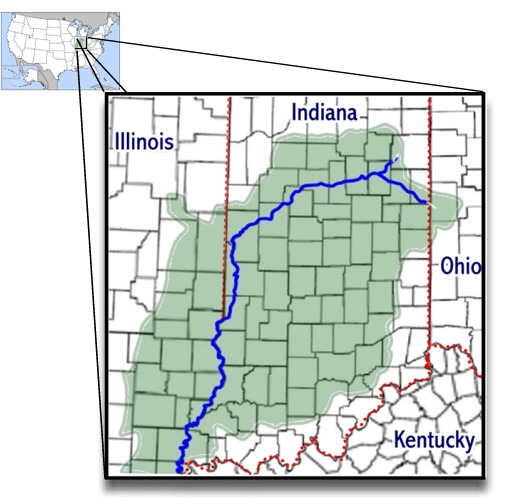

A deliberative discussion occurred in Indiana in 2022 to address the management of a local watershed. A watershed is an area of land that directs rainfall and snowmelt toward local creeks, streams, and rivers. In this case, the watershed spread across four Indiana counties. The discussion was sparked by widespread concern over the poor quality of water entering a nearby creek due to a variety of pollutants, including E. coli from manure spread on adjacent farmland, contamination from improperly installed septic tanks, and litter from people who recreate on the creek. However, stakeholders disagreed about how to best improve the water quality or who to blame.

Consequently, trained facilitators at a nearby college organized a deliberative discussion for a variety of residents and local organizations across the counties. During their discussion, participants produced the following:

- Public knowledge about the issue’s complexity, such as recognizing that both farmers who own nearby land and recreators who canoe on the creek are impacted by the water quality and contribute to its pollution.

- Public judgment when they agreed on an educational approach to preserving the watershed’s health. They determined that educational efforts should also attend to related concerns like soil runoff and animal welfare versus only targeting water quality.

Deliberative Discussions in Historical Context

People in the Western political tradition have historically used deliberative discussions to enact and improve democracy. One of the earliest venues for democratic governance—during the sixth and fifth centuries BCE—was the Athenian Assembly. Greek citizens convened there to raise, discuss, and make decisions about public issues.

Box 16.4 Democratic Participation in the Athenian Assembly

Let’s take a closer look at the Athenian Assembly to understand how the power to participate was shared. The Athenian Assembly met forty times each year on the Pnyx Hill in Athens, Greece. Attendance ranged from three thousand to six thousand citizens. The Pnyx represented the political center of the city-state, in contrast to the Agora marketplace (the social and legal center) and the Acropolis (the religious center with the Parthenon, Erechtheion, and other sacred and ceremonial buildings), which both sat adjacent to the Pnyx. These three—Pnyx, Agora, Acropolis—formed a physical and visual triangle.

Assembly meetings began from the speaker’s platform located on the Pnyx. The presiding officer sacrificed a pig and prayed to the gods. A proposal was then announced, and the presiding officer asked, “Who wishes to speak?” Any topic could be raised during the Assembly meetings, but the majority of topics were set in an agenda constructed by a smaller council. Anyone could speak two times on a single issue, and there was no formal time limit. There were means for keeping long-winded speakers in check, however, such as heckling and, in more extreme cases, shouting the person down. These meetings were often quite boisterous and emotionally expressive. When the moment seemed right, the presiding officer called for a vote. As such, the participants in this democracy had the opportunity to fully engage in listening, speaking, and voting.

Perhaps because of the strengths of such deliberative exchanges, we find movements in the United States that strongly resemble the Athenian precursor, albeit on a smaller scale. Box 16.5 provides several US examples from over the past five centuries! For hundreds of years, Americans have recognized the value of deliberative discussions in North American democratic participation.

Box 16.5 Deliberative Discussions in the United States from the Seventeenth to Twenty-First Centuries

In the seventeenth century, New England colonists developed town hall meetings. These meetings were informally structured, met on an ad hoc basis, and included citizens, town officials, and magistrates. As colonists grew dissatisfied with British rule, town hall meetings became a place to discuss their situation and to deliberate possible actions.

During the nineteenth century, new efforts arose in the United States to promote public discussions and educate our young country’s citizens. The Lyceum movement emerged in the 1820s and lasted until just after the Civil War in the 1860s. Teacher and scientist Josiah Holbrook started the movement and named it after Aristotle’s school in ancient Greece. It provided adult education and a place to discuss public issues.

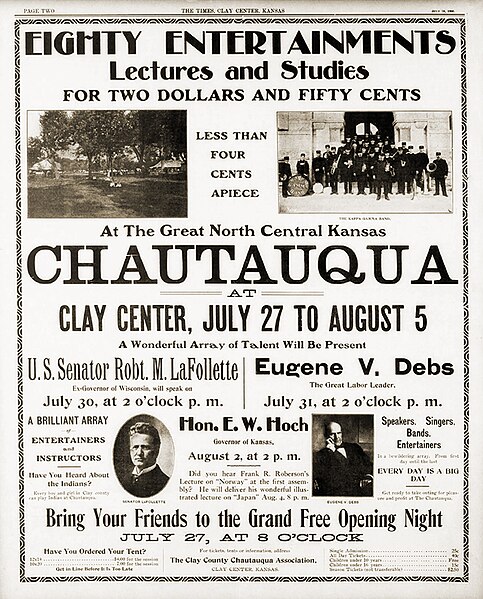

The Chautauqua movement began in 1874 on the heels of the Lyceum movement. It similarly functioned as a kind of adult education that included discussion of civic affairs. It started in New York and spread across the country by 1880. Though most groups disbanded by the 1930s, you can still find Chautauqua meetings today.

The Open Forum movement developed around the same time as the Chautauqua movement. Starting from such established open forums as the Cooper Union in New York City (1894), the Open Forum movement gained popularity across the country during the 1930s. It utilized community discussions to educate and engage adult citizens in social and political topics.

During this same period of the 1920s and 1930s, American academics also grew interested in the role of public discussions. These years correspond with the aftermath of World War I; the Progressive Era when many social reformers attempted to strengthen national democratic practices; and the Great Depression. Some college professors of speech responded to societal concerns by teaching students how to engage in discussions. This added focus increased and extended through the mid-1950s but largely faded out of university curricula by the 1960s (Keith, 2004).

Enthusiasm for deliberative discussions arose again near the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. During the 1980s, increased social fragmentation, political disaffection, and even illiteracy in civic affairs prompted nonprofit organizations like the Charles F. Kettering Foundation and National Issues Forum to focus on teaching, researching, and advancing deliberative discussions. In 2002, the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation became a meeting place for practitioners. As the twenty-first century progressed, several universities and colleges established centers and initiatives to promote deliberative conversations on and off their campuses.

Despite ongoing interest, however, few US residents today have been trained in or experienced a deliberative discussion. Instead, unproductive discourse seems to dominate mainstream communication. Consequently, we focus this chapter on instructions for effectively participating in deliberative discussions. The next chapter offers guidance for facilitating deliberative dialogue.

Unproductive discourse is purposefully sensational public communication designed to promote division and to misrepresent the complexities of public issues.

Participating in a Deliberative Discussion

All participants in a discussion play a role in the outcome. Those who dominate the discussion, block the ideas of others, seek attention for themselves, or engage in excessive sarcasm obviously harm the discussion. Those who participate in the discussion with an open mind, frankness, and sensitivity to others help the discussion thrive. In the following table, we highlight five intellectual virtues—and ways you can adopt them—to practice good participation in a deliberative discussion.

|

Active listening |

|

|

|

Intellectual humility and doubt |

|

|

|

Inclusiveness |

|

|

|

Imagination |

|

|

|

Reflectiveness |

|

|

|

Table 16.1 |

||

Notice that employing the virtues requires actively taking responsibility for the discussion. That might sound surprising. After all, when you are not leading the discussion, it can be tempting to zone out, go along with what others say, or slyly scroll on your phone. Even as a participant, however, you can and should help shape the conversation. That means paying attention, listening ethically (as discussed in chapter 2), and speaking up in ways that embody the five intellectual virtues. When you accept such responsibility, you ensure the group will reap the benefits of deliberative discussions, to which we turn next.

Benefits and Limitations of Deliberative Discussions

The importance of deliberative discussions can hardly be exaggerated. Public deliberation provides us the invaluable opportunity to engage in discussion with those whose opinions differ. When discussing a problem of mutual concern, we realize those who disagree with us are reasonable, engaged individuals. We may even learn that how we characterize such people is untenable.

The importance of deliberative discussions can hardly be exaggerated. Public deliberation provides us the invaluable opportunity to engage in discussion with those whose opinions differ. When discussing a problem of mutual concern, we realize those who disagree with us are reasonable, engaged individuals. We may even learn that how we characterize such people is untenable.

Box 16.6 Humanizing the Opposition

Imagine being a participant in a deliberative discussion about water quality, similar to the Indiana discussion explored in an earlier example. Perhaps you walk in, ready to argue against small-town inhabitants and against environmentalists.

You may discover the following:

- The “local yokel,” for example, turns out to be a third-generation farmer—say, Marcus—who is trying to shift from using chemical pesticides to living organisms to control pests but cannot find sufficient funding.

- The “tree hugger” may be a woman—say, Amanda—who wants to improve water quality so she and her kids can continue to enjoy canoeing together.

When the opposition is given a name and a voice to explain the reasons for their position, we can better connect as people and find more productive ways forward.

Also, while deliberative discussions are hard work, if done well, they result in better decisions. In contrast to when experts or officials make decisions on their own, deliberative discussion allows the public to directly influence community agenda-setting and choices. That is, ordinary residents can influence what topics community leaders attend to and how. Deliberative discussions also help community members avoid the pitfalls of unreflective bias and groupthink. A wiser set of decisions results from sharing opinions and experiences as well as from systematically considering the benefits and drawbacks of every approach.

Deliberative discussions, however, incur limitations as well. While the public sphere is meant to be a gathering of community members to discuss public issues as equal participants, it can actually privilege members with higher social status and increased knowledge of participation norms—such as how the group expects you to talk and behave during a deliberative discussion.

Talk or behavior that falls outside expectations may be shut down or excluded because it’s deemed inappropriate. The inappropriate talk or behavior is often accused of being uncivil—speech that violates decorum because it is disrespectful, angry, and/or impolite. Censorship of uncivil speech can stop dialogue from becoming unproductive or divisive, but it can also be abused by shutting out people with lower social status.

Uncivil speech—rhetoric that violates decorum because it is disrespectful, angry, and/or impolite.

Typically, people in power get to decide when expectations have been violated. What that means is what counts as appropriate behavior for deliberation is not universally or objectively agreed upon, so those in power typically get to decide where to draw the line.

NPR’s Karen Grigsby Bates goes so far as to argue that “pushing back against the status quo will be seen as inherently uncivil by the people who want to maintain it. And there are always higher standards expected of those people pushing back.”

Standards of decorum are drawn through policing discourse, which is the use of rhetoric to determine preferred or appropriate ways of talking together when deliberating public issues. Policing discourse aims to censor the speech of people who challenge the social order.

When used to quell disagreement, policing discourse strategically shifts attention away from the dissent raised (in the cases in and toward the individuals or groups protesting. Consequently, such rhetoric implies that the individuals need to change (or be “civilized”) and that the status quo, including existing systems of inequity, should be maintained.

Deliberative discussion leaders (also known as dialogue facilitators) should, therefore, proceed with sensitivity in light of these limitations and historical abuses.

- One suggestion, which we explore more in the next chapter, is to invite participants to “call out” problematic language while keeping participants in the conversation. In other words, deepen and widen the conversation instead of shutting it down or censoring voices.

- Also, encourage participants to expect productive dialogue to make them uncomfortable. It is likely their assumptions and values will be challenged. They will likely hear perspectives they had not considered and realize their conclusions need to change. They may hear language that makes them upset and need to articulate why. They may also need to listen to others express anger about things they say or solutions they prefer.

If leaders take appropriate steps and participants allow themselves to be uncomfortable, deliberative discussions can model and teach the civic skills people need to productively contribute to their communities. Participating in a discussion teaches participants to listen as much as they talk; to ask questions as well as advocate ideas; to recognize the drawbacks, and not just the benefits, of their ideas; and to consider the consequences of any choice upon a wider range of community members than only themselves.

Conclusion

The ability to discuss civic concerns productively with your fellow residents is an integral aspect of public speaking. This chapter offered you an explanation of the nature, benefits, and US lineage of deliberative discussions. It also provided guidance on how to effectively participate in such discussions, and it warned against calls for civil speech that silence dissenting voices. Leading or participating in a deliberative discussion can result in better decision-making, potentially help you connect with people whose opinions differ from your own, and teach civic skills that people need to productively contribute to their communities.