Arguments and Information

4 Conducting Credible Research

Learning Objectives

- Describe the importance of research

- Explain different information types

- Introduce ways to evaluate research and potential sources

- Describe types of plagiarism and explain best practices in citation

- Consider the impact of generative AI on research and citation practices

What does the word “research” conjure up for you? Do you think about sitting in a library and sorting through books or searching online? Do you picture a particular type of person?

While these images aren’t incorrect (of course libraries are connected with research), “research” can feel like an intimidating process. When does it begin? Where does it happen? When does it stop?

It’s helpful to understand what research is – the process of discovering new knowledge and investigating a topic from different points of view. Research is a process; it’s an ongoing dialogue with information. But, as you know, not all information is neutral, and not all information is ethical. Part of the research process, then, is evaluating information to determine what knowledge is ethical and best suited for your argument. While you (likely) won’t be conducting original research by, for example, asking a research question, crafting a research design, and collecting, analyzing, and interpreting the data, you will be selecting and synthesizing research done by experts to provide evidence for your speeches.

This chapter will focus on the research process and the development of critical thinking skills—or decision-making based on evaluating and critiquing information— to identify, sort, and evaluate (mostly) scholarly information. To begin, we outline why research matters, followed by insights about locating information, evaluating information, and avoiding plagiarism.

Why Research?

Research gets a bad rap. It can feel like a boring, tedious, and overwhelming process. In our current information age, we are guilty of conducting a quick search, finding what we want to read, and moving on. Many of us rarely sit down, allocate time, and commit to digging deep and researching different perspectives about an idea or argument.

But we should.

When conducting research, you get to ask questions and actually find answers. If you have ever wondered what the best strategies are when being interviewed for a job, research will tell you. If you’ve ever wondered what it takes to be a NASCAR driver, an astronaut, a marine biologist, or a university professor, once again, research is one of the easiest ways to find answers to questions you’re interested in knowing.

Research can also open a world you never knew existed. We often find ideas we had never considered and learn facts we never knew when we go through the research process. Maybe you want to learn how to compose music, draw, learn a foreign language, or write a screenplay; research is always the best step toward learning anything.

As public speakers, research will increase your confidence and competence. The more you know, the more you know. The more you research, the more precise your argument, and the clearer the depth of the information becomes.

Box 4.1 Research as a Mindset

To some of us, research means quickly finding internet “hits” to fill a required bibliography or finding evidence to back your position. Neither act really involves research, however. Recall we defined research as the process of discovering new knowledge and investigating a topic from different points of view. That means research initially requires adopting a particular mindset: one that values inquiry and diverse perspectives, clarifies the type and scope of research needed, and slows down to thoughtfully discover appropriate sources.

|

Research as Inquiry |

Research as Strategy |

|

Treats research as an opportunity to educate yourself |

Treats research as a technique to support a predetermined conclusion |

|

Open to discovering perspectives and arguments you had not considered before |

Closed off from potentially compelling reasons to reject or rethink your desired option |

|

Helps you discover or narrow your desired focus |

Blocks you from considering more useful or narrower foci |

|

Strengthens your understanding of the topic |

Reinforces your understanding of the topic |

|

Finds and reviews several different types of sources about the same topic |

Uncritically accepts the first relevant source you find |

|

Community-focused: Helps you locate and advocate the most suitable options for your community |

Self-focused: Helps you promote your preferred option without fully educating yourself on alternatives first |

Where to Start

Because you’ve done exploratory research (as discussed in Chapter 3), you will likely have basic, foundational information about your argument. With that basic information in mind, ask: “what question am I answering? What should I be looking for? What do I need?”

Your specific purpose statement or a working thesis are good places to start. Remember the college textbook affordability example from Chapter 3? To refresh, the specific purpose is: “to persuade my audience to support campus solutions to rising textbook costs.” Research can help zero in on a working thesis by a) finding support for our perspective and b) identifying any specific campus solution that we could advocate for.

When we begin researching, we have three initial questions that arise from our specific purpose: has the cost of college textbooks increased over time? What are the causes? And what are the opportunities to address rising textbook costs in a way that can improve access relatively quickly at your institution?

These are just our starting questions. It’s likely that we’ll revise and research for information as we learn more. As Howard and Taggart point out in their book Research Matters, research is not just a one-and-done task (2010). As you develop your speech, you may realize that you want to address a question or issue that didn’t occur to you during your first round of research, or that you’re missing a key piece of information to support one of your points.

Use these questions, prior experience, and insight from exploratory brainstorming to determine what to search and where to start. If you still feel overwhelmed, that’s OK. Start somewhere (or ask a librarian for help), and use the insights below about information types as a guide.

Locating Effective Research

Once you have a general idea about the basic needs you have for your research, it’s time to start tracking information down. Thankfully, we live in a world that is swimming with information.

As you search, you will naturally be drawn to tools and information types that are already familiar to you. Like most people, you will likely use Google as your first search strategy. As you know, Google isn’t a source, per se: it’s a search engine. It’s the vehicle that, through search terms and savvy wording, will direct you to sources related to those terms.

What information types would you expect to see in your Google search results? We are guessing your list would include: news, blogs, Wikipedia, dictionaries, and social media.

While Google is a great tool, all informational roads don’t lead to Google. Learning about different information types and different ways to access information can expand your search portfolio.

Information Types

As you begin looking for research, an array of information types will be at your disposal.

When you access a piece of information, you should determine what you are looking at. Is it a blog? an online academic journal? an online newspaper? a website for an organization? Will these information types be useful in answering the questions that you’ve identified?

Common helpful information types include websites, scholarly articles, books, and government reports, to name a few. To determine the usefulness of an information type, you should familiarize yourself with what those sources are and their goals.

Information types are often categorized as either academic or nonacademic.

Nonacademic information sources are sometimes also called popular press information sources; their primary purpose is to be read by the general public. Most nonacademic information sources are written at a sixth to eighth-grade reading level, so they are very accessible. Although the information often contained in these sources can be limited, the advantage of using nonacademic sources is that they appeal to a broad, general audience.

Alternatively, academic sources are often (not always) peer-reviewed by like-minded scholars in the field. Academic publications can take longer to publish because academics have established a series of checklists that are required to determine the credibility of the information. Because of this process, it takes a while! That delay can result in nonacademic sources providing information before scholarly academics have tested or studied the phenomena.

In addition, be cognizant of who produces information and who that information is produced for. Table 4.1 simplistically illustrates the producer and audience of our short list of information types.

|

Information Type |

What does it do? |

Who is it produced by? |

Who is it produced for? |

|

News Report |

Inform readers about what’s happening in the world. |

General Public / Journalist |

General Public |

|

Social Media |

Connects individuals, groups, and consumers |

General Public |

General Public |

|

Peer Reviewed Scholarly Journal Article |

Provides insight into an academic discipline |

Academic Researchers/Scholars |

Academic Researchers/Scholar/ Students |

|

Academic Books |

Provides insight into an academic discipline |

Academic researchers/Scholars |

Academic Researchers/Scholars /Students |

|

Government reports |

Shares information on behalf of a government agency |

Government Agencies |

Policy/Decision Makers |

|

Data and Statistics |

Reports statistical findings |

Government Agencies |

Policy/Decision Makers Academic Researcher |

|

E-books |

Inform, persuade, or entertain readers about a topic through a digital medium |

Can be Self-Published or Published through a Scholar / Agency |

General Public |

| Table 4.1 |

This is not an exhaustive list of information types. Others include: encyclopedias, periodicals or blogs.

With any information type, the dichotomy of producer/audience helps us with evaluating the information. As you’ve learned from our discussion of public speaking, the audience informs the message. If you have a clearer idea of who the content is written for, you can determine if that source is best for your research needs.

Having a better understanding of information types is important, but open and closed information systems dictate which source material we have access to.

Open/Closed Information Systems

An open system describes information that is publicly available and accessible. A closed system means information is behind a paywall or requires a subscription.

Let’s consider databases as an example. It’s likely that you’ve searched your library’s database. Databases provide full text periodicals and works that are regularly published. This is a great tool because it can provide you links to scholarly articles, news reports, e-books, and more.

“Does that make databases an open system?” you may be asking. Access to databases is purchased by libraries. The articles and books contained in databases are licensed by publishers to companies, who sell access to this content, which is not freely available elsewhere. So, databases are part of a closed system. The university provides you access, but non-university folks would reach a paywall.

Table 4.2 illustrates whether different information types are like to be openly available or behind a paywall in a closed system. Knowing if an information is type is open or closed might influence your tools and search strategies used to discover and access the information.

|

Information Type |

Open Access |

Closed Access |

|

News Report |

Some content exposed to internet search engines and open |

Licensed content available with subscription or single access payment

|

|

Social Media |

General public and open |

Privacy settings may limit some access |

|

Peer Reviewed Scholarly Journal Article |

Scholarship labeled as “Open access” are free of charge |

Licensed content available with subscription or single access payment

|

|

Academic Books |

“Open access” books are free of charge |

Many books require payment and purchase |

|

Government Reports |

Government information in the public domain is open |

Classified government information – restricted access

|

|

Government Data/Statistics |

Open government data |

Classified government information – restricted access |

| Table 4.2 |

Information isn’t always free. If you are confronted with a closed system, you will have to determine if that information is crucial or if you can access similar information through an openly accessible system.

Having a better understanding of information types and access will assist you in locating research for your argument. We continue our discussion below by diving into best practices for locating and evaluating research.

Hot Tip! For more information on how to use Google and library databases, please click on following links:

Evaluating Research

Going Deeper through Lateral Reading

Imagine that you’re online shopping. You have a pretty clear idea of what you need to buy, and you’ve located the product on a common site. In a perfect world, you could trust the product producer, the site, and the product itself and, without any research, simply click and buy. If you’re like us, however, being a knowledgeable consumer means checking product reviews, looking for similar products, and reading comments about the company. Once we have a deeper understanding of the product and process, then we buy!

Argument research is similar. Feeling literate about the information types described above is key, but inaccurate or untrustworthy content still emerges.

In response, we recommend lateral reading – fact-checking source claims by reading other sites and resources.

Lateral reading emerged after a group of Stanford researchers pitted undergraduates, professors with their Ph.D.s in history, and journalists against each other in a contest to see who could tell if information was fake or real (Wineburg, McGrew, 2017). The results? Journalists identified fake information every time, but the Ph.D.s and undergraduates struggled to sniff out the truth.

Why is this?

Well, journalists rarely read much of the article or website they were evaluating before they dove into researching it. They would read the title and open a new tab to check out if anyone else had published something on the same topic. Reading what other people had written gave the journalists some context or background knowledge on the topic, better positioning them to judge the argument and evidence made. They would circle back to the original article, identify the author, and open more tabs to verify the identity of the author and their credentials to write the piece. Once the journalists were satisfied with this, they had enough background information to start judging the argument of the original piece. Essentially, journalists would read the introduction and pick out big ideas or the argument, people, specific facts, and the evidence referenced in the first paragraph.

Mike Caulfield (2017), a professor who specializes in media literacy, read the Stanford study and identified steps to evaluate sources. One of those steps is to read laterally, and three additional steps include:

- Check for previous work: Look around to see if someone else has already fact-checked the claim or provided a synthesis of research.

- Go upstream to the source: Most web content is not original (especially in an era of artificial intelligence). Go to the original source to understand the trustworthiness and ethos of the information.

- Circle back: If you get lost, hit dead ends, or find yourself going down an increasingly confusing rabbit hole, back up and start over. You’re likely to take a more informed path with different search terms and better decisions.

Let’s apply lateral reading to the college textbook affordability topic from Chapter 3 with the specific purpose to “to persuade my audience to support campus solutions to rising textbook costs.”

You decide to search “textbook affordability” into Google. Google identifies approximately 1 million sources – whoa. Where do you start? Click on one those stories, “Triaging Textbook Costs” – a 2015 publication from Inside Higher Ed. From it, you learn about research on the rising costs of textbooks over time, how some students navigate those costs, and something called “open educational resources” (OER) as a strategy for reducing costs. You’ll use lateral reading to follow up on some of the sources linked in the story and do a little more research to fact check this single source. By searching “OER,” you can verify that yes, many universities are turning to open educational resources to combat textbook affordability. Now, you can dive deeper into OERs as a potential solution to the problem.

While this research is useful, you might also decided that 2015 is slightly outdated since it does not account for major cultural events like COVID or the increased use of e-books. This doesn’t mean that you can’t use the source – it’s given you some great vocabulary and history of the problem – but you may want more updated insights when outlining next steps or talking about the contemporary issues of textbooks in higher education. Lateral reading isn’t about finding the perfect source (which may not exist), it’s about developing critical thinking skills to evaluate what research is the most sound, ethical, and applicable to your presentation context.

Lateral reading is a great tool to verify information and learn more without getting too bogged down. However, your research doesn’t stop there. As you begin compiling information source types around your argument, verify the credibility and make sure you’re taking notes.

Questioning Selected Source Information

Practicing lateral reading will provide you better insight on what diverse sources say about your argument. Through that process, you’ll likely find multiple relevant sources, but is that source best for your argument? Perhaps, but ask yourself the following questions before integrating others’ ideas or research into your argument:

- What’s the date? Remember that timeliness plays a key role in establishing the relevance of your argument to your audience. Although a less timely source may be beneficial, more recent sources are often viewed more credibly and may provide updated information.

- Who is the author / who are the authors? Identify the author(s) and determine their credentials. We also recommend “Googling” an author and checking if there are any red flags that may hint at their bias or lack of credibility. Remember that a qualified author should have credible experience or expertise in the area that you’re researching. Social media has led to the “influencer marketing phenomenon” where popular content creators are conflated with credible experts.

Box 4.2 Types of Source Authority

Authority relates to the expertise, power, or recognized knowledge a source has concerning a topic. Types of authority include:

- Subject Authority: Sources with trained expertise on the topic. A scholar with a PhD in waste management studies would be a subject authority on that topic. Somewhat similarly, the Environmental Protection Agency would also be an authoritative source about environmental effects of landfills, because the agency’s entire work—that is, their subject expertise—focuses solely on environmental concerns. Sources that have also been reviewed by subject experts—such as scholarly publications—carry even more authoritative weight.

- Societal Authority: Emphasizes a source’s power to control outcomes based on their position within a society or organization. Your mayor would be considered an authoritative source, for instance, about your city’s waste management challenges. Similarly, Harvard University’s Office for Sustainability wields societal authority over that university’s reduction, recycling, and disposal of waste.

- Authority from Special Experiences: For instance, a person who grew up in a neighborhood near a hazardous waste site could speak with some authority on that experience. Perhaps they attended town meetings about the site, experienced ill health effects, or could share the site’s effects on their quality of life.

- Who is the publisher? Find out about the publisher. There are great, credible publishers (like the Cato Institute), but fringe or for-profit publishers may be providing information that overtly supports a political cause.

- Do they cite others’ work? Check out the end of the document for a reference page. If you’re using a source with no references, it’s not automatically “bad,” but a reputable reference page means that the author has evidence to support their insights. It helps establish if that author has done their research, too.

- Do others cite the work? Use the lateral reading technique from above to see if other people have cited this work, too. Alternatively, if, as you research, you see the same piece of work over and over, it’s likely seen as a reputable source within that field. So check it out!

It can feel great to find a key piece of information that supports your argument. But a good idea is more than well-written content. To determine if that source is credible, use the questions above to guarantee that you’re selecting the best research for your idea.

Box 4.3 Criteria to Evaluate Sources: Setting a High BAARR

When determining the value and veracity of a source, consider the following criteria. Think of each as a spectrum rather than a box to be checked.

Bias: A predetermined commitment to a particular ideological or political perspective.

- Who are the publishers, sponsors, and/or authors of the source? Who paid for the source’s creation? What can you learn about them?

- How is the source described, such as in an “About” section or mission statement?

- How do other sources describe this source, and where does it fall in the Ad Fontes Media Bias chart or on the AllSides Media Bias chart?

- What evidence of bias, if any, is present in the material itself?

Accuracy: The truthfulness or veracity of the information provided by a source.

- Has the material been reviewed or vetted by an editor or reviewers?

- Does the material line up with information and facts provided by other sources about the same topic? Do a wide variety of parties agree on the same facts?

- Can you find reviews or responses to the material?

Authority: The expertise, power, or recognized knowledge a source has concerning a topic.

- Who is the author, and what type of (relevant) authority do they have, if any?

- Are they an expert on the subject matter? Do they have a title or degree that demonstrates their expertise?

- Does their position in society or an organization lend them authority on the subject?

- Have they had relevant special experiences that authorize the information they provide?

Recency: How up to date the information is that a source provides.

- What is the publication date or the date the material was last updated?

- Have more recent sources appeared that alter or revise the information the source provides?

- Are you using the source to establish a historical fact or to offer a more recent interpretation of a historical occurrence?

Relevance: The degree of association between the source, a speaker’s topic, and their audience.

- Does the source directly address your particular focus on the topic?

- How well will this source resonate with your specific audience?

Take Notes

Remember: this is a lot of stuff to keep track off. We suggest jotting down notes as you go to keep everything straight. Your notes could be a pad of paper next to your laptop or a digital notepad – whatever works best for you. There are numerous free online applications and platforms that can also help you keep track of your notes and source content. Check in with your university library to see what experts in your area recommend or have available, too.

This may seem obvious, but it is often overlooked. Poor note taking or inaccurate notes can be devastating in the long-term. If you forget to write down all the source information, backtracking and trying to re-search to locate citation information is tedious, time-consuming, and inefficient. Without proper citations, your credibility will diminish. Keeping information without correct citations can have disastrous consequences – as discussed below.

Plagiarism

While issues of plagiarism are mostly present in written communication, the practice can also occur in oral communication and in communication studies courses. It can occur when speakers misattribute or fail to cite a source during a speech, or when they are preparing outlines or notecards to deliver their speeches and fail to cite sources.

According to the National Communication Association (NCA), “ethical communication enhances human worth and dignity by fostering truthfulness, fairness, responsibility, personal integrity, and respect for self and others” and truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication (“Credo for Ethical Communication,” 2017). This would imply that through oral communication, there is an expectation that you will credit others with their original thoughts and ideas through citation. One important way that we speak ethically is to use material from others correctly. Occasionally we hear in the news media about a politician or leader who uses the words of other speakers without attribution or of scholars who use pages out of another scholar’s work without consent or citation.

But, why does it matter if a speaker or writer commits plagiarism? Why and how do we judge a speaker as ethical? Why, for example, do we value originality and correct citation of sources in public life as well as the academic world, especially in the United States? These are not new questions, and some of the answers lie in age-old philosophies of communication.

Although there are many ways that you could undermine your ethical stance before an audience, the one that stands out and is committed most commonly in academic contexts is plagiarism. A dictionary definition of plagiarism would be “the act of using another person’s words or ideas without giving credit to that person” (Merriam-Webster, 2015). Plagiarism is often thought of as “copying another’s work or borrowing someone else’s original ideas” (“What is Plagiarism?”, 2014). Plagiarism also includes:

- Turning in someone else’s work as your own;

- Copying words or ideas from someone else without giving credit;

- Failing to put quotation marks around an exact quotation correctly;

- Giving incorrect information about the source of a quotation;

- Changing words but copying the sentence structure of a source without giving credit;

- Copying so many words or ideas from a source that it makes up the majority of your work, whether you give credit or not.

Plagiarism exists outside of the classroom and is a temptation in business, creative endeavors, and politics. However, in the classroom, your instructor will probably take the most immediate action if he or she discovers your plagiarism either from personal experience or through using plagiarism detection (or what is also called “originality checking”) software.

In the business or professional world, plagiarism is never tolerated because using original work without permission (which usually includes paying fees to the author or artist) can end in serious legal action. So, you should always work to correctly provide credit for source information that you’re using.

Important Note! Our understanding of plagiarism is cultural situated and not universally true. The norms around citations and plagiarism that are discussed in this book are grounded in a United States context. These may differ if you travel internationally or write in other cultural contexts. Remember: culture matters for making meaning when we communicate!

Types of Plagiarism

There are many instances of speakers or authors presenting work they claim to be original and their own when it is not. Plagiarism is often done accidentally due to inexperience. To avoid this mistake, let’s work through two types of plagiarism: stealing and sneaking. Sometimes these types of plagiarism are intentional, and sometimes they occur unintentionally (you may not know you are plagiarizing). However, as everyone knows, “Ignorance of the law is not an excuse for breaking it.”

Stealing

No one wants to be the victim of theft; if it has ever happened to you, you know how awful it feels. When someone takes an essay, research paper, speech, or outline completely from another source, whether it is a classmate who submitted it for another instructor, from some sort of online essay writing service, or from elsewhere, this is an act of theft. The wrongness of the act is compounded when someone submits that work in its entirely and labels it as their own.

Most colleges and universities have a policy that penalizes or forbids “self-plagiarism.” This means that you can’t use a paper or outline that you presented in another class a second time. You may think, “How can this be plagiarism if the source is in my works cited page?” The main reason is that by submitting it to your instructor, you are still claiming it is original, first-time work for the assignment in that particular class. Your instructor may not mind if you use some of the same sources from the first time it was submitted, but he or she expects you to follow the instructions for the assignment and prepare an original assignment. In a sense, this situation is also a case of unfairness, since the other students do not have the advantage of having written the paper or outline already.

Sneaking

Instead of taking work as a whole from another source, an individual might copy two out of every three sentences and mix them up so they don’t appear in the same order as in the original work. Perhaps the individual will add a fresh introduction, a personal example or two, and an original conclusion. This kind of plagiarism is easy today due to the Internet and the word processing functions of cutting and pasting. It also most often occurs when someone has waited too long to start a project and it seems easier to cut and paste portions of text than it is to read, understand, and synthesize information into their own words.

You might not view this as stealing, thinking, “I did some research. I looked some stuff up and added some of my own work.” Unfortunately, this is still plagiarism because no source was credited, and the individual “misappropriated” the expression of the ideas as well as the ideas themselves.

Avoiding Plagiarism

To avoid plagiarism, you must give credit to the words, research, or insights of others. When you’re integrating supporting research or using a key idea or theory, let the audience know! As you add research into your outline, you can either:

- Use direct quotes: this means that you’re including information from a source verbatim.

- Paraphrase: express the source’s idea but not verbatim.

- Summarize: explain the main ideas or arguments from the source’s findings.

Citing others will bolster your credibility because it demonstrates that you have in-depth knowledge about the topic.

In English classes, you’ve likely used style guides (like MLA or APA) to ethically cite research in an essay. Continue this practice. Regardless of how you’re integrating that research – verbatim or paraphrasing—the source reference should appear both in the writing and through an oral citation.

Source Documentation

Once you have found strong sources for your topic—whether through Google, your college library, or interviews—how do you properly and effectively credit them in your speech? We next answer this question by considering how to document your sources during a speech and in an associated bibliography. We will begin by explaining the importance of source documentation.

Better Safe Than Sorry

Whenever you get ideas from, directly quote, paraphrase, or summarize content from another source, cite your source. A citation provides a source’s basic identifying information, such as the four W’s we discuss in below “What to Cite: The Four W’s.”

Citing your sources strengthens your credibility because it reflects your competence (you did your homework) and trustworthiness (you are making clear what sources you consulted). In contrast, passing off someone else’s ideas as your own (i.e., not citing your sources) is an act of academic dishonesty and plagiarism. It is unethical to take credit for other people’s ideas or work. You will lose your audience’s and instructor’s trust. Furthermore, not citing your sources makes it more difficult for your audience to learn more about your topic and take action. By citing your sources, you provide them with a path forward to further education and advocacy.

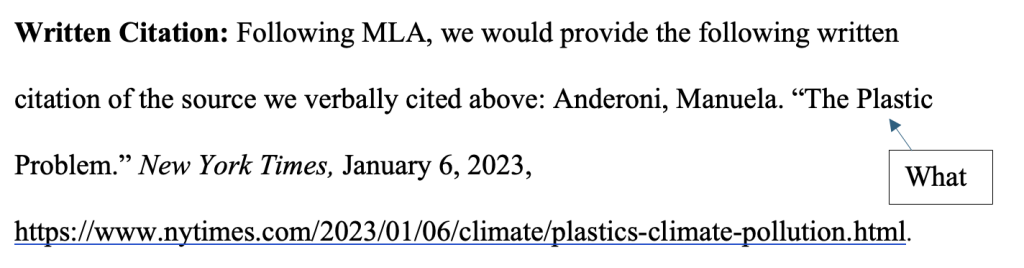

Written and Verbal Citations

When preparing a public speech, keep in mind two types of citations: written and verbal. Written citations are written down, typically in the form of a bibliography (perhaps called a Works Cited or References)—much like you might provide with an essay you have written. Your instructor may require you to submit a written bibliography with your speech outline or manuscript. Alternatively, you may choose to provide your bibliography to a community group you are addressing so they can further pursue the topic you discuss.

Written citations should follow a style guide, or instructions for writing and formatting sources. Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) both author style guides. Ask your instructor what style guide they prefer and consult Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab (known as “Purdue OWL”) for help following it. Your library likely has access to both print and online style guides, and your reference librarians can help you with citation questions. Alternatively, free software such as Zotero may prove useful.

Speakers should also use verbal citations, because audiences don’t typically receive or read a bibliography, or they don’t see it (such as on a concluding visual aid) until after the speech is over. Consequently, speakers should use verbal citations, which are vocalized during the speech. They can be integrated anywhere into a speech: as part of the attention-getter, to establish the problem, to make a viable solution compelling, and so on. Wherever you include them, say the verbal citation prior to summarizing, paraphrasing, or quoting the source. Announcing the source first allows the audience to evaluate the information in light of its source.

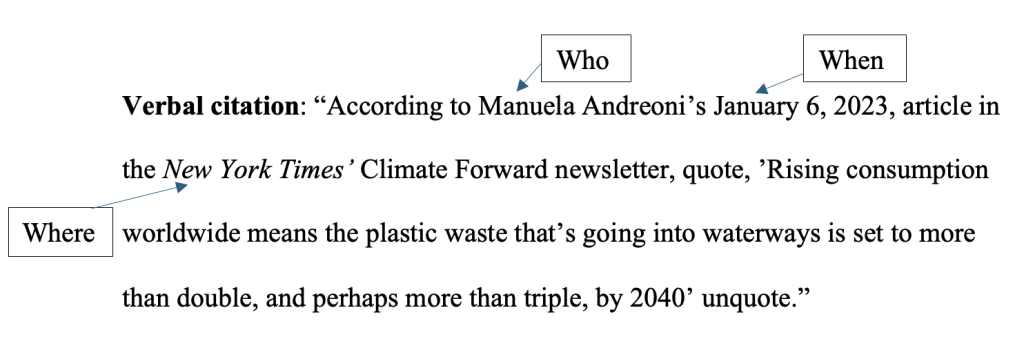

What to Cite: The Four W’s

While specific requirements differ based on the exact type of source, most written and verbal citations need you to answer the four W’s: who, where, when, and what.

- Who created the source? That is, who is the author of the article, post, or book, or who did you interview?

- Where was it published? What is the title of the journal or website, for instance, where the article or blog can be found? Alternatively, how did you conduct the interview (by email or in person)?

- When was the source published or made available, or when did you talk with your interview subject?

Answering the three questions of “who,” “where,” and “when” is sufficient for an oral citation, but a fourth question—“what”—may also be necessary for a written citation in a bibliography.

- What is the name of the source? In other words, what is the title of the article, book chapter, or post? This is more specific than the publication (“where”).

Box 4.4 Examples of Citing the Four W’s

Notice the use of the words “quote” and “unquote” to verbally indicate where the source’s direct language begins and ends.

Notice both citations answer who, where, and when. Only the written citation additionally answers what and provides a URL (if relevant). Neither of these are included in a verbal citation.

Considerations Regarding Generative AI and Research

As you embark on the research process, you may be asking: what about artificial intelligence (AI)? Is that an information type? Is it a “source”? To answer this question, we’ll focus primarily on generative AI tools, or tools that use “a machine-learning model that is trained to create new data” (Zewe, 2023, para. 4). You may be most familiar with Chat GPT – a generative AI tool created from Open AI – where you can prompt the tool to create content based on an algorithm that scans an enormous amount of data. As a student at UMD, you also have access TerpAI.

Box 4.5 TerpAI

“TerpAI is a powerful GenAI tool designed to simplify your interactions with technology and enhance your daily tasks. Acting as your digital assistant, thought partner, and educational resource, TerpAI helps you manage projects and research topics and get quick answers with ease. It’s invaluable for students and educators, providing clarity on complex concepts and assisting with study guides and lesson plans. As a thought partner, TerpAI offers insights that improve decision-making, whether you’re brainstorming ideas or analyzing data. Seamlessly integrating into your existing digital environment, TerpAI is secure and reliable, ensuring your data is handled with the highest privacy standards. With TerpAI, you can work smarter, learn more effectively, and make confident decisions.”

Be sure to familiarize yourself with the University’s guidance on GenAI use.

The use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in the research and writing process is a highly debated issue, and we understand why! Learning how to be an ethical and engaging public speaker requires that you learn how to engage, sort, and critically understand research to create original speeches that are written by and sound like you. If you over-rely on generative AI (Like Chat GPT) to compose the content of a speech, you’re missing out on a valuable part of the learning process. This means that, in your public speaking class, your instructor might completely prohibit the use of generative AI.

However, your instructor may allow some AI engagement. If you are integrating generative AI into your speech, it’s important to cite it. Remember that citations are a signal that you didn’t create the work, so integrating a citation for a piece of generative AI just makes sense! Otherwise, you are presenting information “as your own,” resulting in an unethical practice.

Box 4.6: Sources Versus Compilers

A source is an original communication product that has been written by one or more human authors and published for an audience. A book, a news article, and a speech are all sources.

A compiler is a service that gathers information from multiple sources and makes it available. Two types of compilers that students often confuse with sources are research databases and artificial intelligence (AI).

Many types of AI exist, but at its core, AI draws on, retrieves, and compiles scores of sources to produce content. The content is prompted by a user’s questions (while using an AI chatbot) or search terms (while using a search engine like Google). The output—such as the paragraphs an AI chatbot writes in response to your request or the images an AI text-to-image generator might produce—can make AI appear like a source. However, AI is not a source as we have defined it. It is not human, and it does not (yet) produce original communication as we—your authors—think of originality.

Instead, machine-learning AI uses algorithms that very quickly analyze existing data from myriad sources to find patterns—which is the compiling function—and then predict a useful or appropriate response. AI may assemble the predicted content in novel or unique ways, but it is based on the sources and data that AI draws on.

PCMag’s K. Thor Jensen explained the shortcomings of generative AI: “Computers aren’t capable of what we would consider original thought—they just recombine existing data in a variety of ways. That output might be novel and interesting, but it isn’t unique” (Jensen, 2023).

AI’s function as a robust compiler rather than a source helps explain why it tends to unreflectively repeat the dominant racist, sexist, and homophobic biases and stereotypes commonly found in existing sources (Olheiser, 2023; Tiku et al., 2023)—and why you are more likely to encounter factual errors when using generative AI. According to PCMag’s K. Thor Jensen, the datasets AI trains on become outdated and reflect societal biases.

Jensen also points to two additional factors for AI’s errors: the complexity of AI’s coding, which prevents our ability to trace the source of an inaccurate response to correct it, and AI’s requirement to produce a response to your query even if it does not have the answer.

What Can a Generative AI Model Tell Us?

Further, people can use AI to deliberately produce false videos or recordings of famous people, for instance, doing or saying things that never occurred. While many of these fakes are produced in good fun (like hearing Adele’s version of a Beatles’ song), the technology can easily be used more maliciously to trick audiences into believing falsehoods.

Therefore, we warn you to not rely on AI for your research. Not only is it a compiler rather than a source, but it also risks being inaccurate or used purposefully to deceive. Moreover, unlike traditional information types, the content that generative AI produces is not retrievable by your audience. In other words, if you cite a website, the audience can locate and look up that website to either verify your research or to learn more. But with generative AI, your audience can’t go back to the source and verify the information.

Having said that, AI can help you get started on a speech by functioning as a feedback tool. You might use AI to brainstorm arguments and counterpoints. It can also help you restate complex ideas more clearly and produce effective visual aids. If you want to use AI in any of these ways,

- consult your instructor and/or librarian to discuss if and how you can use AI,

- consider the ethical implications involved in doing so

- explicitly acknowledge your use of AI by citing which tool you used and how

- double-check any sources AI cites to ensure they actually exist and provide useful information, and

- find additional sources and develop and synthesize the ideas you gain on your own.

AI Hallucinates Research Sources

As AI becomes more popular and powerful, students increasingly turn to chatbots for their research. As you probably already know, among the information that an AI chatbot can compile are research sources.

If you ask ChatGPT for “a list of specific sources about excessive waste management,” for example, it will provide five or so. The ease and efficiency of this service is terrific, but be careful! AI chatbots can “hallucinate,” or make up, sources that do not exist.

“In addition to potentially providing false information, ChatGPT can produce legitimate looking reference citations for materials that don’t exist” (Los Alamos National Laboratory Research Library).

Box 4.7 AI Hallucinates Research Sources

When we asked for specific sources about excessive waste, most of what ChatGPT provided did not exist.

- It named The Waste Land: A History of Waste Management by Elizabeth A. M. McKenzie, published by Routledge in 2019, but that full title does not appear on Routledge’s site, Amazon, or Google Scholar.

- Similarly, ChatGPT listed a scholarly article by John Smith titled “Excessive Waste: A Global Perspective” and published in 2021 in the Journal of Environmental Studies, volume 34, issue 2. This journal does exist, but its volume 34 was published in 2024 (not 2021), that volume only consists of issue number 1 (so there is no issue 2), and John Smith does not appear in the journal’s list of authors published.

Others have run into similar problems with AI chatbots hallucinating research sources (Emsley, 2023).

AI chatbots will get smarter with time and therefore should offer more accurate references and hallucinate less. Nonetheless, if you choose to use an AI chatbot to find research sources, it will always be your responsibility to (1) make sure the sources provided actually exist and (2) find the sources and read them. Research is the process of learning about a topic by discovering what credible sources have said, written, or recorded about it. Finding and documenting sources are means toward the end of that learning, not ends in themselves.

Box 4.8 Benefits & Drawbacks of Generative AI

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

| Speed & convenience

Generative AI uses an algorithm to find an answer to a prompt that is often easy to understand. |

Not retrievable

Your audience can’t go back to the source and verify the information |

| Safety

AI can feel like a low-stakes and nonjudgmental conversation partner

|

Bias

AI uses algorithms that pull from a vast pit of online data (created by humans); thus, it will replicate human biases. Ferrare (2023) warns that “bias in generative AI systems can come from a variety of sources. Problematic training data can associate certain occupations with specific genders or perpetuate racial biases” (para. 7). |

| Inaccurate/false research

Generative AI bypasses best practices like fact checking or verifying scholarly research, resulting in misinformation (Endert, 2024) and hallucinates sources |

Citing the Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools

You might be wondering: ok, but how do I cite a piece of text or an image that was AI generated? That depends on what citation style guide you’re using:

- APA: If you use APA, they’ve created a resource about citing generative AI, with a specific focus on Chat GPT. Generally, they recommend being transparent by disclosing where and how AI was used, using an in-text citation, and listing its use in your reference page. Here’s an example of how you would cite Chat GPT content in the outline of a speech and in the reference page:

- In the outline: “When given the prompt, ‘is generative AI a credible academic source?’ the Chat GPT generated text’s summarized its answer by noting that “while generative AI can produce text and other content, it is generally not considered a credible academic source on its own. However, it can be a tool to assist in research and creativity, and the outputs it generates can be used as a starting point for further investigation and verification” (OpenAI, 2024).

- In the reference page: OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT (June 26 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

- MLA: MLA includes similar suggestions in its current (2024) citation requirements and, like APA, suggests a) citing any generated content that is quoted or paraphrased, b) acknowledging how you used the tool (i.e. to translate), and c) vetting any source, fact, or insight generated.

Generative AI (and AI in general) are quickly impacting our learning environment, and these rules could change, too! In any case, make sure you are checking your syllabus, assignment descriptions, and following up with your instructor about their specific AI policy.

Box 4.9 Citing the Use of AI Tools

To cite your use of AI, you should name the following elements (not necessarily in this order):

- the AI tool and version you used (e.g., ChatGPT 4.5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, DALL-E 3.0),

- the company who made the tool (e.g., OpenAI, Google),

- the date you used the tool,

- what you used it for or what you asked it to do, and

- a URL to the tool.

For example, “Provide a list of specific sources about excessive waste” prompt. ChatGPT 4.5, OpenAI, 17 April 2025, https://chatgpt.com/.

Remember: Always check with your instructor as well as style guides for current recommendations.

Key Takeaways

Conclusion

Having a strong research foundation will give your speech interest and credibility. This chapter has shown you how to access information but also how to find reliable information and evaluate it.

This process may seem exhausting at first, but you likely already are doing this in your everyday life. We simply are asking you to be a bit more aware of and practice lateral reading. Doing so will help you better understand the context and judge the veracity of an author’s argument and their evidence. It will also likely give you plenty of new evidence to inform your own argument.