Arguments and Information

8 Outlining

Learning Objectives

- Identify the benefits of outlining

- Construct a preparation outline

- Use a presentation outline for an extemporaneous delivery

- Create a manuscript for a manuscript delivery

- Choose a medium for speaking notes

In the previous chapter, we discussed the importance of organizing your speech. We also named elements to include in your speech, such as an introduction, main points, and a conclusion. You may be wondering, “How will I know if I’ve included everything I need?” or “How can I see if my points make sense together?”

This chapter answers these questions by exploring the basics of outlining. An outline is a sketch or condensed version of your speech. First, we will focus on the preparation outline, which is the draft you write as you plan and organize your speech. It includes all your arguments, support, transitions, and citations. It helps you know if your points cohere together and if there are any gaps. Much of the hard but rewarding work of speech writing occurs while constructing and revising the preparation outline. When you are ready to practice delivering your speech, you will also need a presentation outline, which we discuss in the latter half of this chapter. This will include tips for preparing your speaking notes (or manuscript) depending on your chosen mode of delivery, including what medium you should use.

We begin by considering the importance of outlining for you and your audience. When we refer to the audience in this chapter, we mean your direct audience, who we described in chapter 2 as the people who are exposed to and attend to your speech.

The Importance of Outlining

You may be tempted to avoid outlining and instead write your speech in free form or as an essay. We urge you to reconsider. Writing a well-crafted outline offers at least three benefits for speakers and audiences: It makes your speech more compelling, helps you identify and improve problems, and aids your memory of your speech.

First, a preparation outline helps you arrange your ideas and supporting evidence in the most compelling manner. When you write a speech in free form, you can quickly lose your way and very quickly lose your audience too. Drafting your speech as an outline helps you focus on your thesis and visualize the linear or nonlinear arrangement you’ve chosen to support the thesis.

Second, the preparation outline helps you diagnose and address potential problem areas in your speech. The outline form allows you to locate points of repetition, gaps in reasoning, or extraneous information. You can more quickly determine if your main points are well balanced and if you have remembered to include an introduction and conclusion.

Finally, a presentation outline provides a visual representation of the speech, which helps you learn the speech. You can easily see your main points, so they become more memorable to you. You can also observe how transitions help you move from one point to another and how the introduction and conclusion open and close the speech.

Time spent constructing, arranging, and revising your speech outline now can reward you later, when audience members join your cause and have a clear sense of how to proceed. Outlining is the work you do to learn your speech, to know it well, and to communicate that deep knowledge to your audience. If you put the time in, it will show.

The presidential speechwriter Peggy Noonan said of speech preparation, “If you find yourself doing draft after draft, this is good. As you write and rewrite you are unconsciously absorbing, picking up your own rhythm and phrasing. This will show itself in a greater ease, a greater engagement when you stand up and give the speech. People will know that you know your text” (Noonan, 1998, p. 24).

There are several specific guidelines that will help you write your preparation outline. Many instructors have strict requirements about how preparation outlines should look and what elements should be included, so be certain to check with your professor about their preferred format before you turn in your document. In the following section, we recommend general principles to follow when outlining.

The Principles of Outlining

The outlining system we present here is widely employed in public speaking courses, because it provides a visual representation of the structure of your speech. This visuality helps you see the relationship among your ideas, making the structure easier to develop and revise.

The outlining system we present here is widely employed in public speaking courses, because it provides a visual representation of the structure of your speech. This visuality helps you see the relationship among your ideas, making the structure easier to develop and revise.

Consistent Indentation and Symbolization

Make sure your outline is structured with a consistent pattern of symbols and indentations. Adopt a pattern of symbols that helps you visually differentiate main points from subpoints and quickly count the number of each. Avoid bullet points because they make these tasks much harder. Instead, main points should be identified by increasing Roman numerals, subpoints by sequential capital letters, and sub-subpoints by rising Arabic numerals. In addition, adopt a pattern of indentations to further distinguish types of points. Each Roman numeral should be flush left, each subpoint should be indented once, and sub-subpoints should be indented twice, as box 8.1 makes clear.

Box 8.1 Sample Indentation and Symbolization

Notice how each point uses sequential symbols (I, A, 1) and spacing (indentation or lack thereof).

I. First main point

A. First subpoint

B. Second subpoint

II. Second main point

A. First subpoint

1. First sub-subpoint

2. Second sub-subpoint

B. Second subpoint

III. Third main point and so on…

Indentation and symbolization help you see the flow of your speech and the relationship among your ideas. You can quickly observe, for instance, what your three main points are. You might discover an idea is not really a main point and functions better as additional support for a main point. This visual relationship among ideas is built on the principle of subordination.

Subordination

Subordination is the practice of making material that is less important, or primarily supportive, secondary to more central ideas and claims. Material in your outline should descend in order of importance. That is, supporting ideas or evidence should be listed under main points and indented.

Noting subordination is much different than writing an essay where subpoints are typically written with the claim they support as a single paragraph. Typically, paragraphs should be avoided when outlining. The subpoints instead should be visually subordinated.

Box 8.2 Sample Subordination

As Javon worked on his deliberation speech, he wanted to list the “benefits” and “drawbacks” of each potential solution or approach to the problem of concussions. These points he labeled “B” (benefits) and “C” (drawbacks). Underneath each of these points, and indented, he gave more detail about what the benefits and what the drawbacks were. This portion of his outline read as follows:

B. This approach foregrounds two benefits.

1. It tries to address the unhealthy aspects of hypermasculinity within football culture, like ignoring pain and ignoring the recovery protocols that may slow the chances of repeated concussion.

2. The education extends beyond players and coaches to include parents, fans, and community members who often perpetuate attitudes that celebrate players for sacrificing their bodies for the game.

C. But there are also drawbacks to this approach.

Here we see that points 1 and 2 are each listed under the claim “This approach foregrounds two benefits.” That’s because the individual examples of benefits (1 and 2) are subordinate to and support the claim that benefits exist (A). The drawbacks will similarly follow as points 1 and 2 under C. Subordination is closely related to the next principle of outlining: coordination.

Coordination

Coordination is a visual representation of the proper relationship between ideas. It is related to subordination because it stresses that ideas of similar importance should be on the same level of the outline.

Box 8.3 Sample Coordination

Here is an example from Riley’s speech, discussing how members of the community can help spread awareness about animal abuse:

1. Use social media to broadcast pet news in our county.

a. Spread news about pet abuse and neglect to broaden awareness of this issue.

b. Spread news about current laws protecting animals.

c. Publicize agencies and phone numbers residents can call if they witness abuse or neglect.

d. Follow the Montgomery County Humane Society on Instagram and “like” them on Facebook.

Here we see coordination in that the four ways for community members to volunteer at the local animal shelter are listed on the same level of the outline: Each has a lowercase letter, each refers to subpoint 1, and each has identical indentation.

After you have sketched the subordination and coordination in your outline, you can turn to another important outlining principle: parallelism.

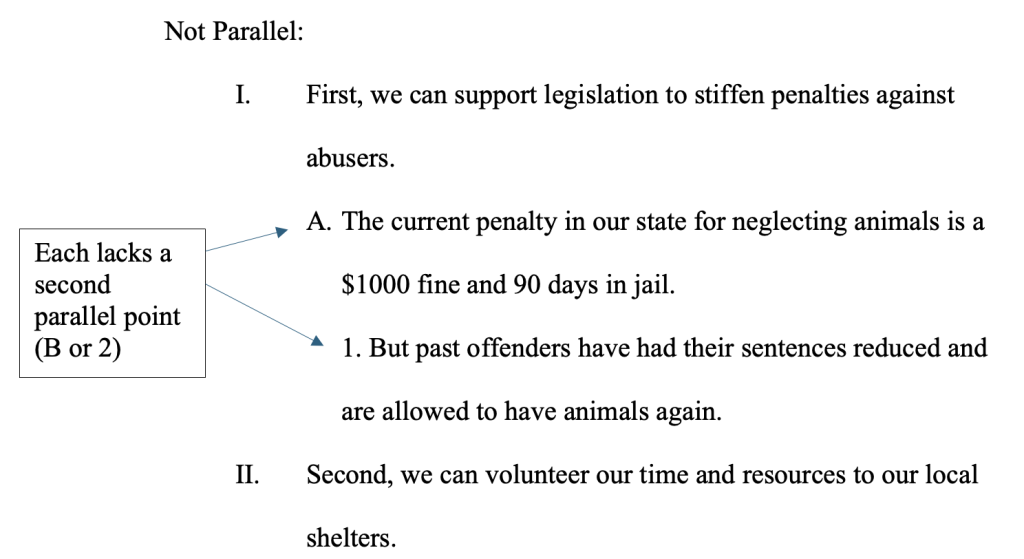

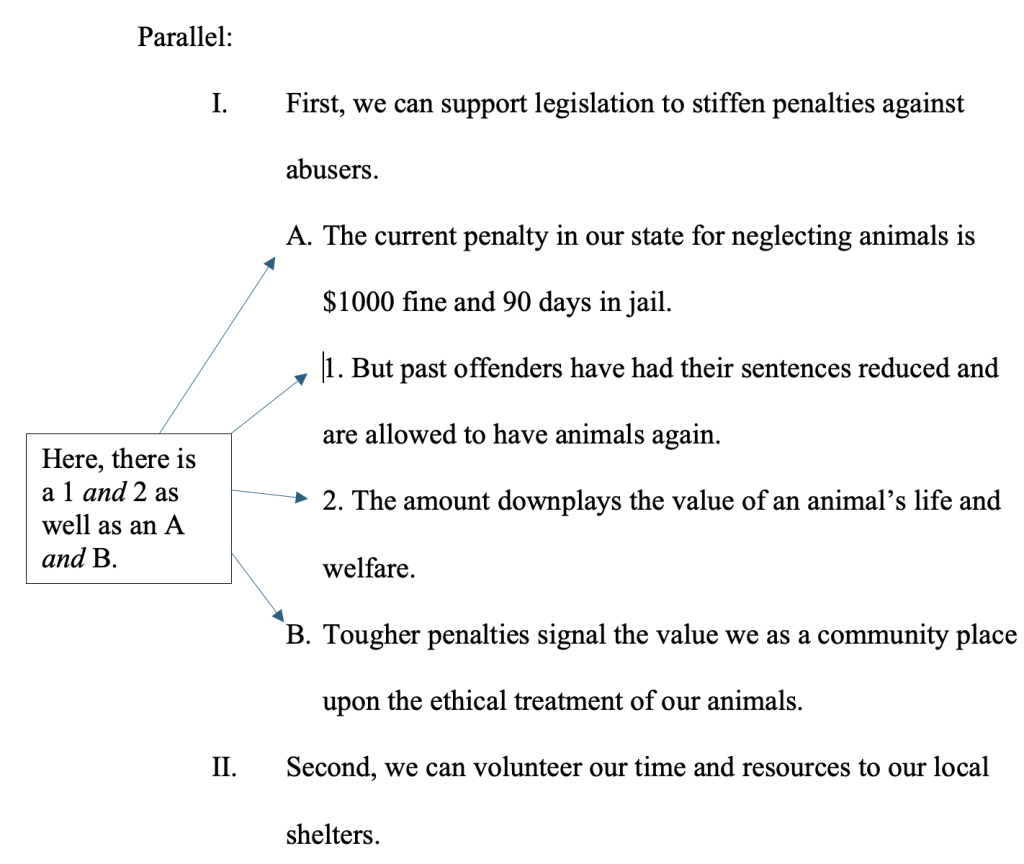

Parallelism

The parallelism principle dictates that you balance your points and subpoints as you divide them. Just as you cannot balance two ends of a scale with only one object, each level of your outline needs at least two points to be in balance or to justify the subdivision.

To explain this concept another way, we often say when it comes to outlining, “every little one has a little two.” In other words, there must be at least two relevant and worthy subordinate ideas to make the subdivision; otherwise, the division is not warranted.

Box 8.4 Sample Parallelism

Parallelism can best be illustrated through contrasting examples. Notice how the first example violates the principle of parallelism twice. Both subpoint A and sub-subpoint 1 lack a pair for balance. The second example provides such balance by adding subpoint B (to balance A) and sub-subpoint 2 (to balance 1).

Balance

The final principle of outlining is balance. Balance in speech outlining dictates each main idea receives roughly the same amount of time and attention in the speech. If the first main point of your speech lasts three minutes, the second main point lasts thirty-seven seconds, and the final main point is four minutes, then the audience suspects that your second “main” point really isn’t that important. An outline helps you visually detect such situations, because you can see how much or how little support you have included for each main point. If you find yourself with unbalanced points, consider adding or subtracting material to balance them.

Now that we have explained the guiding principles that will help you construct a coherent outline, we turn to the specific tasks of writing the preparation outline.

Constructing the Preparation Outline

As we said, the preparation outline is designed to help you think through and develop your speech. In a public speaking course, it is generally the version of a speech that you submit to your instructor, perhaps to receive feedback before you deliver the speech. Your preparation outline will be too detailed to serve as the notes you use to deliver your final speech, but writing a preparation outline is essential to the thinking and planning process. Unless your professor tells you otherwise, preparation outlines should include the following elements.

State Your Specific Purpose

The purpose statement is related to, but not the same as, your thesis statement. Another way to think of the purpose statement is as the overarching goal or objective for your speech. Since you are using this textbook, your purpose will likely be either informative or persuasive, so the verb you choose should reflect the goal (“explain” or “inform” versus “advocate” or “persuade”). Clearly label your purpose statement at the top of your outline. Here is Riley’s purpose statement.

Purpose statement: To urge audience members to become animal welfare educators in our county.

You will not state the purpose statement to your audience, but knowing and succinctly stating your purpose can help you write a good speech. If you do not know what you want your speech to accomplish, there is a good chance the rest of your speech will betray that lack of purpose.

Label Key Components of the Speech: Introduction, Conclusion, Thesis, Transitions

Visually highlight key components of the speech by labeling them in the outline. This helps you easily find them and better ensures they will fulfill their roles. The key components include the introduction and conclusion as well as the thesis and transitions.

First, clearly label the “Introduction” and “Conclusion” by writing those words with the Roman numeral assigned to each. Do not add any other information to the Roman numeral. Instead, the content of these points should appear below the Roman numeral and be indented to show subordination.

Second, label your “thesis” with that word whenever it appears in the outline. We discussed the characteristics of strong thesis statements at length in chapter 12. In your outline, labeling your thesis clearly will help you (and your professor) diagnose whether your central idea is well developed and is fully supported by the main points and subpoints.

The thesis’s location may depend on whether your speech is thesis driven or thesis seeking as we distinguished in chapter 3. If your speech is thesis driven, meaning the thesis “drives” or determines the route the speech will take, then the thesis will likely appear within both the introduction and conclusion (and should be labeled in each). If your speech is thesis seeking, meaning the introduction and main points build up to or “seek” a thesis, it is likely to appear only within the last main point and/or conclusion.

Box 8.5 Sample Labeling of the Introduction and Thesis in a Preparation Outline

Here is the introduction to Riley’s speech on animal welfare. Notice that only the label “Introduction” appears with Roman numeral I. The same would be true for the Conclusion, but with a different Roman numeral. Also notice that the thesis is noted as such, since it is a major speech component.

I. Introduction

A. In 2020, the Netflix documentary series Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem, and Madness aired and became widely popular.

B. Many of you may have heard of or even watched Tiger King, or you may have laughed at parodies and memes of Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin. But how many of us focused on the animals who were treated cruelly?

C. Today I want to talk about this issue that is of great importance to me and I know to many of you as well. I’m an animal lover, and I became aware of pet abuse in our county through my volunteer work at the animal shelter. I was saddened by the Tiger King story and was motivated to do something locally.

D. (Thesis) There are several ways to support our local animal control agency’s power to remove and care for abused animals in Montgomery County, but the most important thing you can do is to increase awareness in our county so more people know what counts as abuse and how to report it.

E. In my speech, I will: first establish the problem of animal neglect and cruelty in our county and state. Next, I will examine a frequently proposed solution and tell you why it will not make an immediate difference in the lives of our animal friends. Then I will advocate my preferred approach of educating the public about animal abuse, and I’ll tell you specific ways you can help spread the word.

Third, label each “transition” between main points by using that word. Transitions are crucial to how an audience makes sense of and follows your speech as you progress. Labeling your transitions in a preparation outline ensures that you include them and can find them easily. It also helps you evaluate the connections between main points and the flow of your reasoning.

Box 8.6 Sample Labeling of Transitions in a Preparation Outline

Within their speech, Riley included this transition to shift from the problem to an alternative solution:

* (Transition) Having addressed the problem of animal cruelty in our county and state, I will now turn to a potential solution to this problem.

Notice that “Transition” is explicitly labeled to draw attention to its presence and function.

Write Main Points, Subpoints, and Transitions in Complete Sentences

Except for the introduction and conclusion, which begin with only their labels, you should write every main point, subpoint, and transition as a full sentence. This is only true for the preparation outline because it helps you plan and organize your speech. Writing full sentences at this stage is a way to discipline yourself to complete your thought and fully prepare what you will say in your speech. Later, after you have developed your preparation outline and are ready to create speaking notes, you can remove full sentences and use keywords and phrases instead. We provide guidance on preparing speaking notes in the later part of this chapter.

Include Verbal and Written Citations

As we explained in chapter 4, providing full citations for all your sources is a sign of ethical and responsible speech writing. That starts with the preparation outline. Include verbal citations—the source citations you plan to vocalize during the speech—in the outline itself. Add them wherever you plan to verbally cite a source. Refer to chapter 4 for the specific information to cite each time.

In addition, include written citations within your preparation outline and at the end of this outline. Within the outline, add a written citation whenever you orally cite or draw information from a source. Each such written citation will likely appear similar to an in-text citation you might add to an essay. At the end of your preparation outline, on a separate last page, include a bibliography (or it might be called Works Cited  or References). Be sure to check with your instructor about their preferred style guide (Modern Language Association, American Psychological Association, etc.).

or References). Be sure to check with your instructor about their preferred style guide (Modern Language Association, American Psychological Association, etc.).

Now that we have explained each element of the preparation outline, we encourage you to look at a full sample preparation outline for an informative speech in Appendix A. Once you have constructed a full sketch of your speech in the form of a preparation outline, you will need to pair your outline down into less detailed speaking notes for the purpose of effective delivery. That is where the presentation outline comes in.

Presentation Outlines

When you are ready to practice delivering your speech, you might wonder what to include in your speaking notes. The answer depends on what kind of delivery you plan to adopt. In chapter 10, we describe four modes of delivery: extemporaneous, impromptu, memorized, and manuscript. Two of these typically require no speaking notes. Speakers delivering impromptu speeches develop their speeches as they speak, though they might jot down a note or two just before speaking. Memorized speeches should, by definition, be committed to memory and thus similarly require no speaking notes.

The other two modes of delivery—extemporaneous and manuscript—do necessitate written words to speak from. As we discuss in more depth in chapter 10, in a manuscript delivery, the speaker writes the entire address and utilizes the text in delivering the speech. In that same chapter, we define an extemporaneous delivery as when a speaker uses trimmed-down notes to recall the speech’s structure, key ideas, and any direct quotations or source citations.

This remainder of this chapter focuses first on how to prepare speaking notes for an extemporaneous delivery. We then offer tips for preparing a manuscript for a manuscript delivery. We end by helping you consider what medium to use for your notes or manuscript.

Preparing a Presentation Outline for an Extemporaneous Delivery

Typically, an extemporaneous delivery will use trimmed-down notes, or what we call a presentation outline. A presentation outline is a brief sketch of your speech designed to help you deliver your speech as free from your notes as possible. It allows you to more easily make on-the-fly adjustments and connect with your direct audience.

Let’s explore four qualities of the presentation outline: It maintains visual cues from the preparation outline; it is brief, though some elements are written out; and it should include delivery notes. To see each of these qualities in use, there is a sample presentation outline in Appendix B.

Maintain Visual Cues from the Preparation Outline

Recall that, in the first half of this chapter, we talked about your preparation outline, or the draft you write as you plan and organize your speech. We instructed you to adopt specific outlining principles for that outline and to include labels for such key components as the introduction, conclusion, transitions, and thesis.

The presentation outline keeps these visual cues and labels. Specifically, it visually shows the structure of your speech by retaining the outlining symbols and indentations. That way, you can quickly glance at the page, locate your place in the speech, and find the information you are looking for. The visual structure can also provide a brief reminder of where you are going next. If you don’t maintain symbols and indentation, you are forced to read through dense text or a full paragraph to find the section you are looking for.

Strive for Brevity

The presentation outline replaces full sentences with keywords or phrases that jog your memory about your points or information, as box 8.7 demonstrates. That means you find your specific wording or expression in the moment. The keywords are simply there to prompt the ideas so you can choose your wording as you go. Consequently, your wording will change slightly each time you deliver your speech using your presentation outline.

Box 8.7 Sample Presentation Outline Excerpt

Imagine delivering an extemporaneous speech on the subsection “Maintain Visual Cues from the Preparation Outline.” The presentation outline for that section might look like this:

A. Maintain visual cues from preparation outline

1. Preparation outline: principles, visual labels

2. Presentation outline:

a. Keep principles, labels

b. Visually show structure by outlining symbols, indentation

c. Can glance, locate information; find where to go next

d. If not, forced to read

Notice how few words appear on each line—just enough to prompt the speaker’s memory of what point or idea they want to convey.

Choosing brevity prevents you from reading your speech and encourages you instead to connect with your audience. Otherwise, if you write too much down, the temptation to read can be overwhelming, especially when you feel nervous.

Write Out Minimal Elements

Even in a presentation outline, you will still want to fully write out a few elements of the speech. These include your thesis, quotations, and verbal citations because accuracy is particularly important for each. In the sample presentation outline in appendix B, you will notice several occasions where these elements are written out. Just keep to a minimum the speech elements you fully write out or, again, you will likely end up reading your speech.

Include Delivery Notes

As you practice your speech, you may receive feedback that you consistently mumble a phrase or you tend to read quotations too quickly for an audience to follow. You may find you have trouble pronouncing a word or you leave out one subpoint repeatedly. All this information is useful as you write your presentation outline.

You can include delivery notes to help yourself through problem spots. Highlight the point you tend to skip. Write out the difficult word phonetically. Remind yourself to “slow down here!” or “pause” in places where those elements of delivery will help your audience absorb the full impact of your words. Again, you can find examples of this in the sample presentation outline in appendix b.

If you observe the four qualities of a presentation outline, you will more likely succeed in delivering your speech extemporaneously. A presentation outline might even help you with other types of deliveries. You could use it in case your memory goes blank while delivering a memorized speech or to jot down some ideas a few seconds or minutes before delivering an impromptu speech. If delivering a manuscript speech, however, you should approach your speech text differently.

Preparing a Manuscript for a Manuscript Delivery

A manuscript delivery requires a manuscript—a fully written-out version of your speech. Unlike a presentation outline, a manuscript typically looks more like an essay. Thus, it will likely include paragraphs rather than indentations, outlining symbols, or labels.

A manuscript delivery may seem rather easy. Just read your text. However, you still need to achieve the three goals of an effective speech delivery established in chapter 10: engage the direct audience, enhance your ideas, and strengthen your credibility. If you don’t adequately prepare your manuscript, simply reading your speech is more likely to bore your audience, distract from your ideas, and harm your credibility.

How, then, can you prepare a manuscript for an effective delivery? We recommend you alter your manuscript in the following ways to aid your success (and as demonstrated in box 8.8):

- Double-space the typed text and use a larger font (16, 18, or 20 point) so you can find your place more easily when you look down.

- Use such visual cues as underlining, bolding, or highlighting keywords or sentences to help draw your attention to them. Such cues enable you to maintain some eye contact with the audience while reducing the risk of losing your place.

- Include prompts or reminders in the manuscript to enhance your vocal and nonverbal delivery, such as your pronunciation, tone, volume adjustments, and pauses.

Box 8.8 Sample Manuscript Excerpt

If you delivered a manuscript speech of the very first paragraph of “Preparing a Manuscript for a Manuscript Delivery,” the manuscript might look like this:

A manuscript delivery [LOUDER] requires a manuscript—a fully written–out version of your speech. [PAUSE] Unlike a presentation outline, a manuscript typically appears [SLOWER] more like an essay. Thus, it will likely include paragraphs rather than indentations, outlining symbols, or labels.

Choose the Medium for Your Presentation Outline or Manuscript

With the evolution of technology, it is hard to recommend one preferred medium or means of communication. Should you print your presentation outline or manuscript onto paper or note cards? Or should you read or glance at them from a tablet, phone, or laptop?

To decide, learn as much about your speaking situation as possible:

- Will you have a podium? If so, note cards can rest easily and rather noiselessly there.

- Will it be a windy, outdoor setting? Perhaps a tablet or paper printout is better.

- Will you speak from a seated position, such as at a conference? Then speaking from a laptop might be ideal.

In general, we recommend against using your phone for speaking notes, since the screen size is harder to read and can fit less text, prompting you to continually look at your phone and scroll down.

In addition to the speaking situation, consider what you find most reliable and comfortable. Perhaps you prefer note cards for a presentation outline because their size forces you to include brief notes. Maybe you like speaking from sheets of paper (especially tucked inside a professional-looking folder) so you don’t have to change pages as often. Some speakers like the convenience of a digital tablet so they never worry about getting their note cards mixed up or losing a page. Whatever medium you choose, it is important to practice using your notes or manuscript.

Practice with Your Chosen Notes and Medium

It is hard to exaggerate the importance of practice, especially when sharpening your delivery. Practice with the medium you have chosen for your notes or manuscript. The experience of speaking from your laptop can be very different from printed pages you hold. Practicing ahead of time will help you find the best medium for you.

Also practice with your presentation outline or manuscript. When delivering from your presentation outline, you may discover you need to add words because you are forgetting your points. Perhaps, instead, you need to remove words because you are relying too much on your notes. You might find one section overly confusing and need to rethink it. Similarly, practicing with your manuscript will help you find the easiest font size for you to read from and where you need to add or remove visual cues.

Practicing with your presentation outline or manuscript ahead of your actual speech delivery leaves you time to make necessary adjustments. If you wait until just before your speech to produce your speaking notes or manuscript, you may run into difficulties while delivering it for your audience.

Conclusion

This chapter stressed the importance of outlining and described general outlining principles that best produce a visual depiction of your organizational structure. It explained the usefulness of a preparation outline and how best to construct one for your speech. This chapter also covered presentation outlines and manuscripts. Now you know what to include in your speaking notes (or manuscript) and how to use your notes for effective speech delivery.

Hot Tip! Don’t forget to check out Appendix A for a sample preparation outline and Appendix B for a sample presentation outline.